A History of the Hajji Baba Club

Rugs in the City

Hajji Baba Club History from the book Timbuktu to Tibet, Chapter 1

by Thomas Farnham

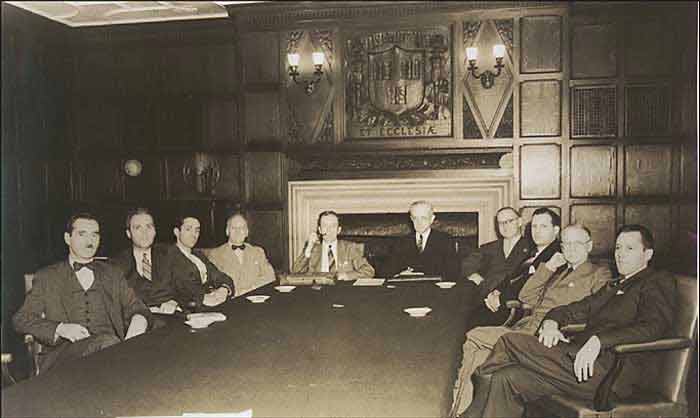

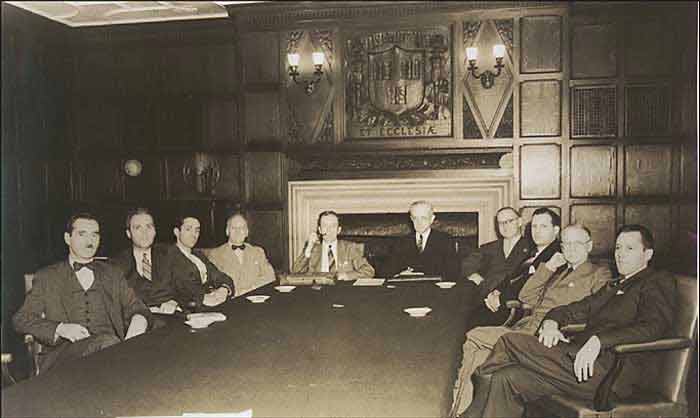

A meeting of the Hajji Babas with Arthur Arwine at the head of the table (center, right), circa 1940

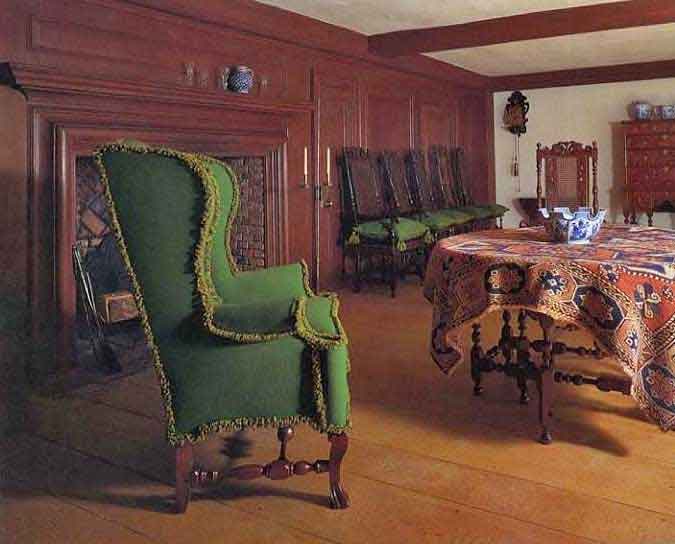

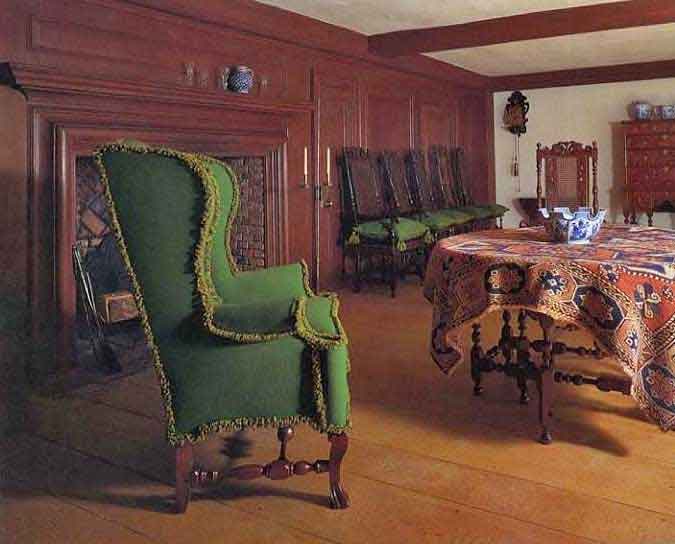

The New York Oriental rug craze began in the eighteenth century. At that time, very few rugs traveled across the many miles from the East to the United States. They were treasured and valued but not well understood; considered too precious to put on the floor, the rugs were used only on top of tables,

and they were all known as ‘Turkey carpitts’ no matter where they had actually been made. Their typical use is illustrated in the seventeenth-century Wentworth Room, brought from a house in New Hampshire and reassembled at the Metropolitan Museum.

This room is furnished with period pieces, and includes a kilim placed on the dining table. In the late nineteenth century, the twin forces of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of western imperialism brought an upsurge in the interest in carpets. As the countries of Europe spread into such regions as Iran, Turkey and Central Asia,

adventurous travelers started to collect antiques from these areas, including rugs and exquisite examples of pottery, glass and metalwork, all of which became popular in home decor. Dealers realized the potential of the western market and also started to collect objects to sell in galleries in Europe and America.

The Industrial Revolution and the wealth it brought spurred this market and in fact demand exceeded the supply of historical carpets; in the late nineteenth century there was an increase in the production of new rugs in Central Asia, in some cases under the sponsorship of European carpet companies. This period also witnessed the development of the field of Islamic art as an academic discipline, at this time mostly driven by collectors; it would be integrated into universities later in the following century.

The phenomenon of world’s fairs and international exhibitions also emerged in relationship to the Industrial Revolution, as a medium to teach eastern design principles to designers working for the factories of London, Paris and Vienna. The fairs were also intended to attract a wider audience, including tableaux of Moroccan homes or Persian bazaars createed to introduce Eastern pop culture to the European, and later the American, public. Another purpose of the fairs was to sell the manufactures of each participating nation.

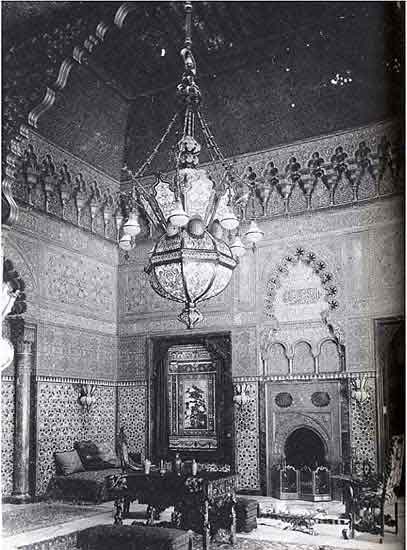

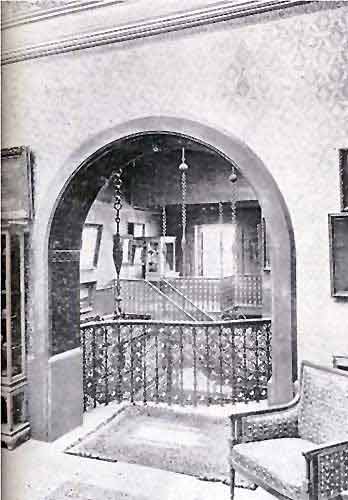

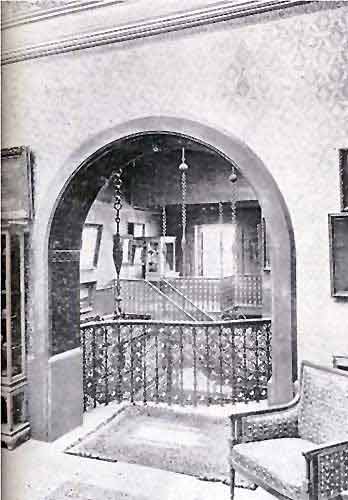

The ‘oriental themed’ residence of the Havemeyers,

The ‘oriental themed’ residence of the Havemeyers,

collectors of Islamic art and carpets.

The first major exhibition in the United States was held in Chicago in 1893, and included a large Persian pavilion and recreated villages from Turkey and Morocco. Several more exhibitions were held throughout the country over the next few years, culminating in the 1939 New York World’s Fair, in Flushing. The latter included a Turkish pavilion where carpets and rugs were sold.

Many of the dealers who set up booths at these exhibitions then started galleries in America’s major cities. In New York, most of these stores were run by Armenian immigrants and concentrated in lower and mid-town Manhattan. At the turn of the century, the most successful belonged to Dikran Kelekian, Hagop Kevorkian, S. Kent Costikyan and H. Michaelyan.

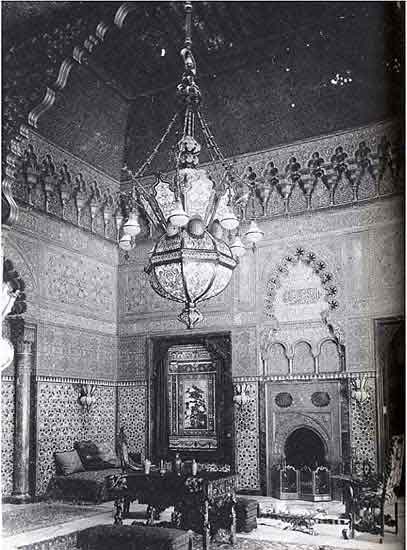

The Vanderbilt Home, New York City

From the dealers downtown, the rugs traveled to the majestic mansions uptown. Some of New York’s biggest businessmen were avid collectors. The Vanderbilt home on Fifth Avenue, for instance, had a ‘Moorish’ smoking room, decorated with a mélange of North African, Turkish and Persian objects. Louis Comfort Tiffany designed his parents’ home at Madison and 72nd, which included a

top-floor apartment for himself and a smoking room similar to the Vanderbilts’. Tiffany also designed an Oriental-themed dining room for the Havemeyers, who resided at 1 East 66th and who were great New York collectors of Islamic art. The room formed the perfect backdrop for the display of part of their own collection of Eastern rugs.

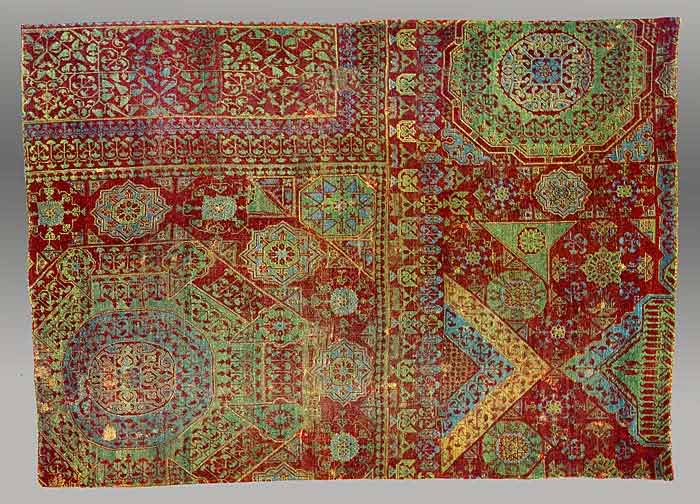

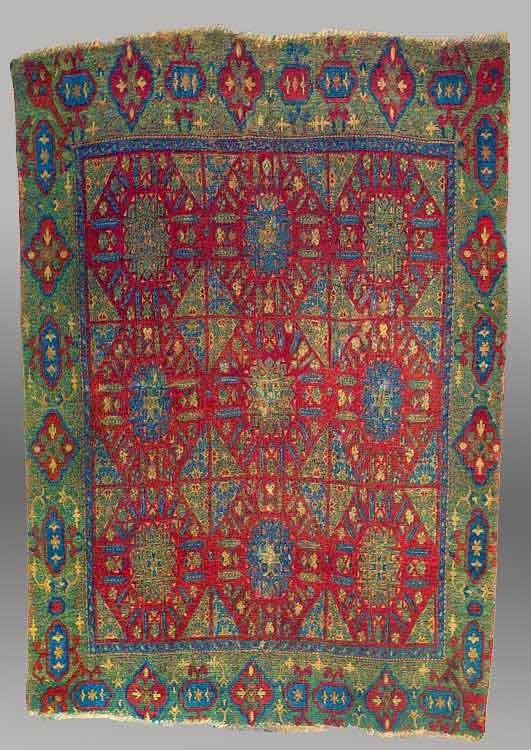

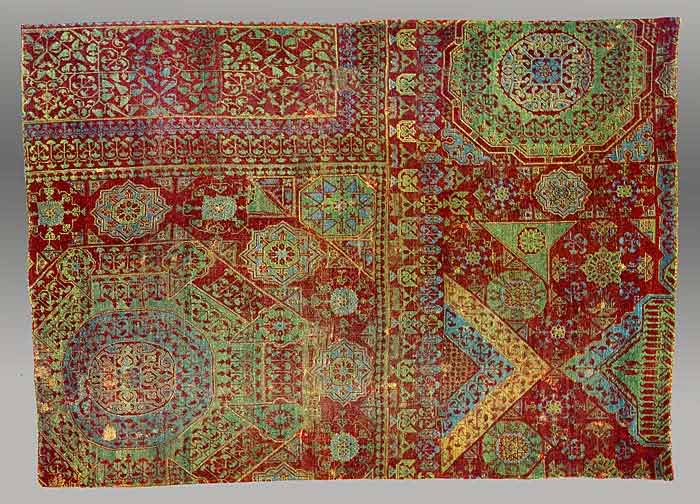

Mamluk Rug fragment, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Given 1971

(former McMullen Collection)

Over the next few years even those New Yorkers living on a more modest budget became interested in Oriental rugs, and as the field of interior decorating arose as a way to help New Yorkers inject a bit of personality into their uniform apartments, each decorator formulated precepts for incorporating the now ubiquitous Oriental rugs into a

well designed, modern home. Discussions can be found in such diverse works as Edith Wharton’s The Decoration of Houses (1897), Lippincott’s Oriental Rugs (1911, part of the Practical Books for the Enrichment of Home Life series), and Amy Rolfe’s Interior Decorating for the Small Home (1917).

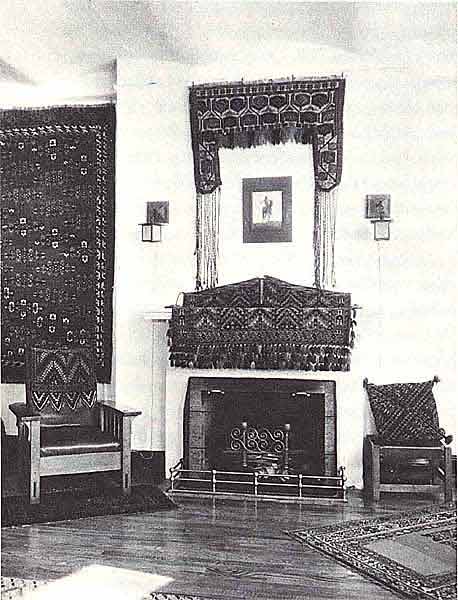

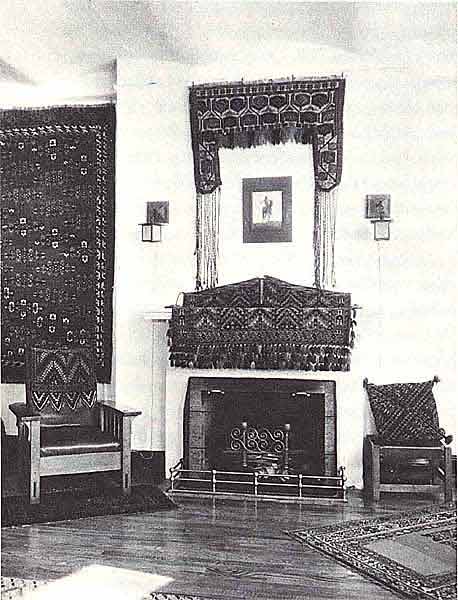

Home of Arthur Arwine, New York, circa 1935

Out of this milieu was born the Hajji Baba Club, but members of this group were not merely looking for an interesting way to decorate. They were experts and aficionados; they traveled far and wide to seek out specific patterns to complete their collections and spent small fortunes to obtain them. The club was formed in 1932, and early meetings were held in an apartment designed to recreate the setting from where the rugs came: Sheridan Square as Turkman yurt, and the home of Arthur Arwine,

engineer. The other founding members were Roy Winton and Arthur Gale, both involved in aspects of the film industry, Anton Lau, another engineer, and Arthur Dilley, the scholar and dealer whose interest was his full-time job. Soon to join the rapidly expanding club were engineer Joseph McMullan, who amassed perhaps the most impressive collection of the group, and Maurice Dimand, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

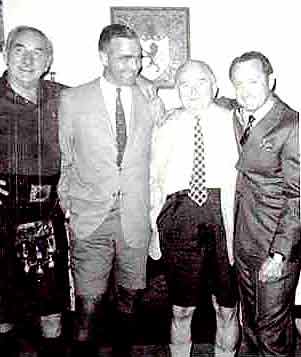

Arthur Arwine, one of the original members of the Hajji Baba Club

The main purpose of the meetings was to closely study the rugs, both reflecting the earlier trend of scholar-collectors and furthering it by changing how we view the rugs today: not merely as decorative items but important cultural artifacts that can also be admired for their artistic quality.

Members now, meeting at the National Arts Club in Gramercy Park, are still involved in advancing scholarship on these textiles, publishing their own collections and hosting lectures by rug scholars from all over the world.

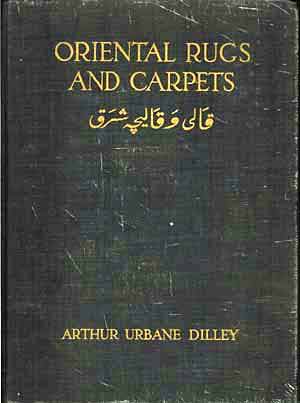

Arthur Dilley, author of “Oriental Rugs and Carpets”.

The club has always been equally concerned with public outreach, and interesting Americans in the less well-known genre of village and nomad rugs. Several members published pioneering studies on the history and classification of rugs, and were also sympathetic to the concerns of most New Yorkers—how to choose and then care for these valuable textiles. Dilley’s Oriental Rugs and Carpets (1931), for instance, contained important

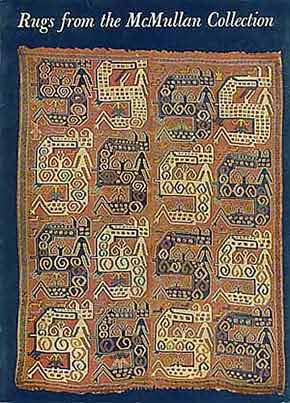

information on connoisseurship, production techniques, and a concluding chapter on decorating. McMullan also contributed to this body of literature with scholarly works such as the Islamic Carpets catalogue (1965), and lighter essays like “Rugs from the East for Homes of the West,” published in 101 Ideas for Successful Interiors (1939)

Joseph McMullan (extreme left in kilts) with

W. Russel Pickering, H. McCoy Jones & Ralph Yohe

He and fellow Hajji Amos Thacher were also very influential in promoting Central Asian and Turkish village rugs, more within the means of the average collector than the Mughal, Safavid or Ottoman carpets bought by the likes of the Morgans and Rockefellers. Their influence is reflected in the composition of today’s museum and private collections, which include textiles produced for both ends of this spectrum.

Today, interest in the ‘Oriental rug’ has expanded from knotted-pile carpets produced for the major Eastern royal courts to include textiles produced through a variety of techniques, such as kilims, tapestry-woven shawls, embroideries and costume pieces, and those made by nomadic and village weavers for their own use rather than for the courts.

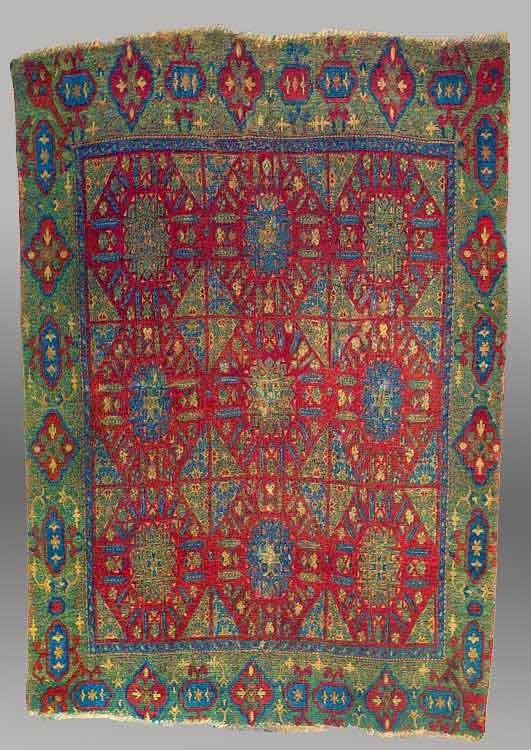

Mamluk Rug, late 16th century, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Given 1969 (former McMullen Collection)

In addition to publication, a major part of the club’s mission has always been to hold exhibitions. From Steppe to Salon will thus join a series of important shows the club has already organized, including those at the Textile Museum (From the Bosporus to

Samarkand, 1969), Baruch College (A Skein Through Time, 1996), a 50th anniversary show at the Asia Society (Oriental Rugs of the Hajji Babas, 1982), and most recently at Sotheby’s (Keshte, 2003)

Objects owned by current members of the Club will form the core of the exhibition, with a few select loans of the important court pieces now in museum collections, and their organization will reflect the current academic approach to Islamic textiles. To this end, the exhibition will be arranged thematically rather than

chronologically. The textiles will be organized by mode of production, either palace/urban or village/nomadic, so as to make apparent the flow of influence in both directions and across wide swaths of geographic territory. Simultaneously, the objects will be organized by function.

A meeting of the Hajji Baba Club, 1965. Charles Grant Ellis is pictured, center, left

Each of the textiles to be displayed had a utilitarian aspect, and one of the aims of the show will be to demonstrate this, through explanatory text and photographs of comparable pieces as used in tent construction, for storage and as animal trappings. In addition, the show will incorporate photographs

depicting the homes of prominent New Yorkers from the early 1900’s, including those of the club’s founding members, to explore America’s initial understanding of Oriental rugs. Photographs will also demonstrate how such objects were originally made available in New York, through new galleries and various Worlds’ Fairs.

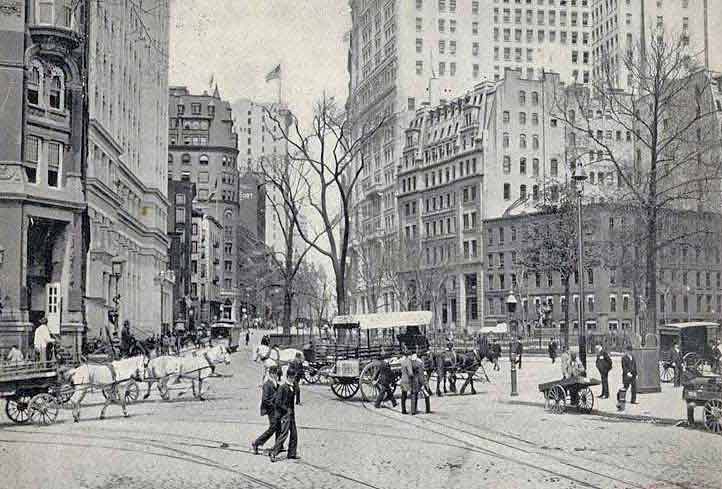

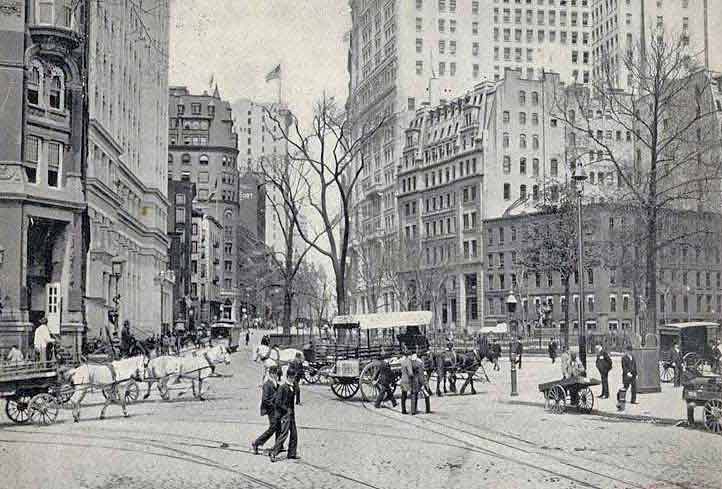

The beginnings of Broadway, 1899

Photo Courtesy www.skyscrapercity.com

Original Founding Members of the NY Hajji Baba Club

Joseph V. McMullan, vice-president, Naylor Pipe Company, 3116 Chrysler Building, New York

Harold I. Oliver, president, Speyer & Company, 24-26 Pine Street, New York

Alvin Pearson, president, Lehman Corporation, 1 William Street, New York

Arthur U. Pope, director, American Inst. for Persian Art and Archaeology, 724 Fifth Ave, New York

Julian C. Levi, architect, 205 West 57th Street, New York

Amos B. Thacher. executive, New York Telephone Company, 101 Willoughby Street, Brooklyn

Roy W. Winton, managing director, Amateur Cinema League, 400 Lexington Avenue, New York

Allen O. Whipple, physician, Medical Center, 620 West 168th Street, New York

Maurice Dimand, Curator, Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Arthur L. Gale, editor, Movie Makers, 400 Lexington Avenue, New York

Arthur J. Arwine, consulting engineer, New York

Anton S. Lau, architect, 101 Park Avenue, New York

Arthur U. Dilley, oriental art scholar and lecturer, 32 East 57th Street, New York

The ‘oriental themed’ residence of the Havemeyers,

The ‘oriental themed’ residence of the Havemeyers,