Rugs in the City – Seventy-five Years of the Hajji Baba Club of New York

Thomas J. Farnham

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

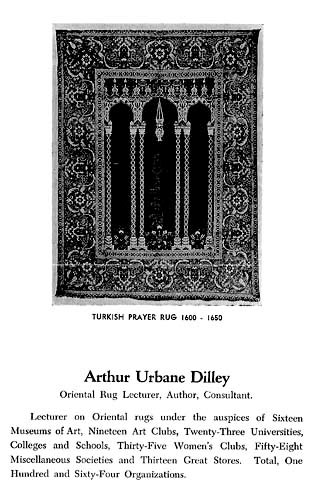

In the preface to her 1966 history of the Hajji Baba Club, a volume that has been of enormous help to me, Olive Olmstead Foster explained her reasons for writing it: “After the death, in October 1959, of Arthur Urbane Dilley, the founder and prime mover of the Hajji Baba Club, the officers expressed the wish that a factual history of the Club might be compiled. My offer to undertake this assignment was accepted.”

As I have examined this same topic, my perspective has been different from Mrs Foster’s. While I was obviously

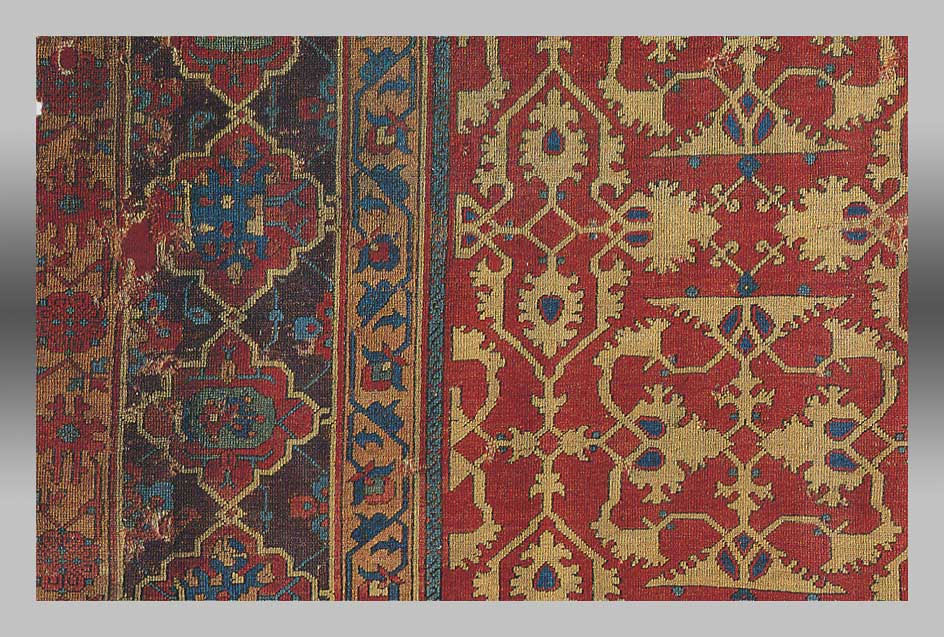

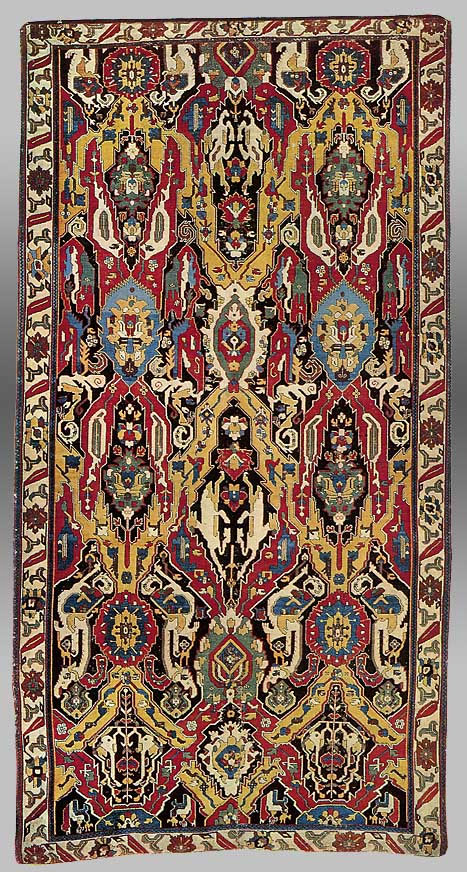

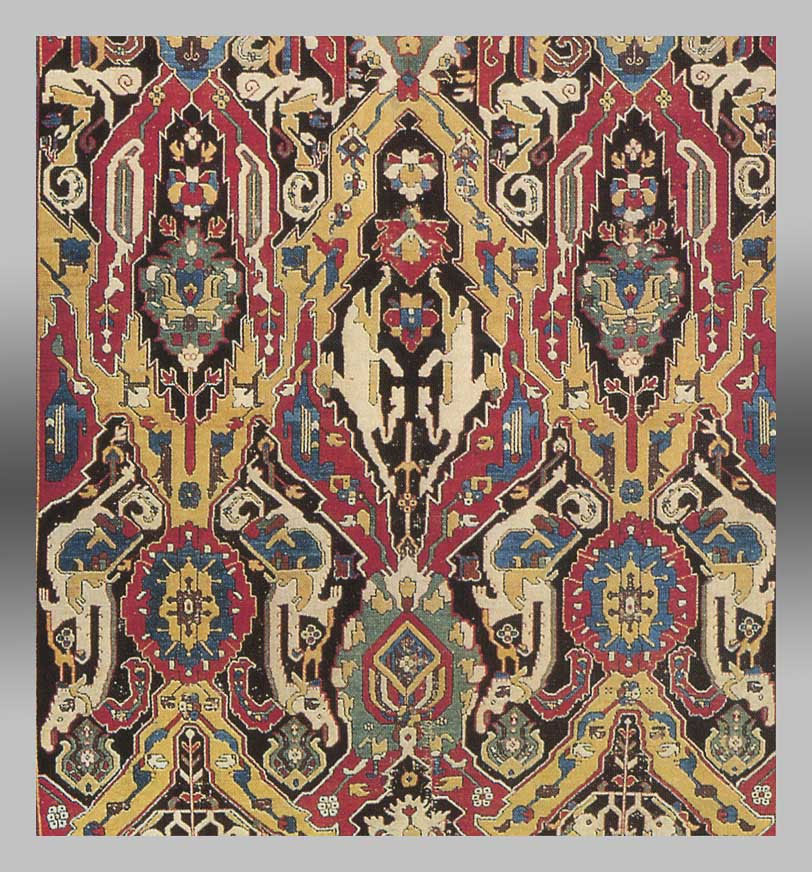

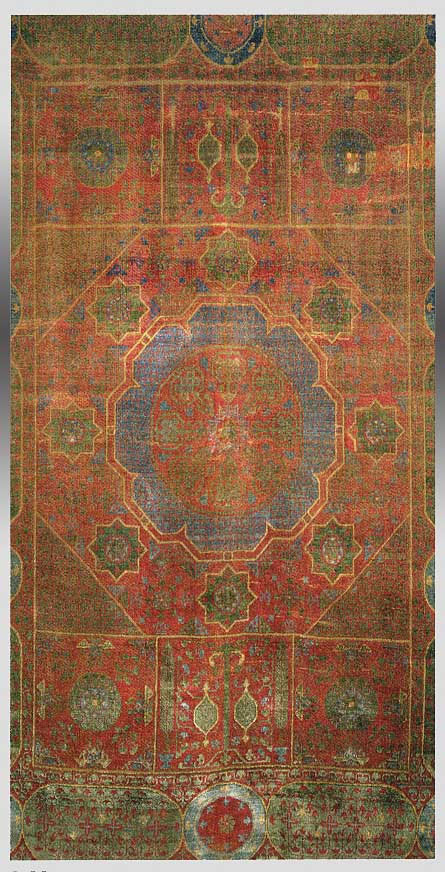

1.1 Detail of plate 107, ‘Kuba’ Carpet, shown to the Hajji Baba Club in 1940.

1.1 Detail of plate 107, ‘Kuba’ Carpet, shown to the Hajji Baba Club in 1940.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Gift of Joseph V. McMullan, 1956, no. 56.217.

To examine the history of a club whose most noteworthy achievement was to have provided some extraordinarily good times for its members, as commendable as that might be, would, from my point of view, be essentially a waste of time. The history of the Hajji Baba Club is, I am convinced, the history of a serious and significant organisation. Certainly its members have enjoyed and still do enjoy each other’s company – in many instances to the point of establishing life-long friendships. Furthermore the Hajjis have been and continue to be excited and edified by the programmes presented at the Club meetings. But these factors, while obviously vital parts of the Club’s appeal, are not what make it important. It is important because, as my research has led me to believe, it has initiated important changes in the ways collectors look at antique Oriental carpets.

I am not a zealous carpet collector, but I do have a keen interest in the changing tastes of those who are. Understanding these changing preferences requires acknowledging that taste hinges on much more than taste. By that I mean changing attitudes about the desirability of certain carpets are often the result of factors that are unrelated to the carpets themselves. Choices that are at first glance highly personal are often not that at all. Particular individuals play an important role in promoting changes in taste. Specifically, dealers have performed a much larger part than many collectors are willing to acknowledge.

Without endorsing a simple conspiracy theory, one cannot overlook the question of possession and gain. The great nineteenth-century Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini could acquire Classical carpets for little more than pocket change and, because of his reputation as ‘the prince of the antiquarians’, could sell them for prices that placed them beyond the reach of all but the very wealthy.

attention. Great dealers can and have made judgments that change the aesthetic hierarchy. Scholars too have been influential. By 1932, when the Hajji Baba Club came into

being, certain carpets had already been canonised. These were, as those familiar with the subject will agree, Classical Persian, Indian, and ‘Persian-style’ Turkish carpets, by which I mean Turkish carpets that were not too ‘Turkish’ in character, most likely Ottoman court carpets. While this was completely in line with Bardini’s opinions, reached in the 1870s and with which other dealers in subsequent decades would agree, these carpets became only fully sanctified when the organisers of the Vienna Carpet Exhibition of 1891, and various art historians, in particular Wilhelm Bode and Alois Riegl, reaffirmed that verdict in their pioneering studies.Collectors, as a group, obviously play an essential role in confirming the opinions of dealers and scholars; clearly if collectors, the people with the cheque books, refused to listen to the opinions of dealers and scholars, those opinions would be meaningless. On certain occasions individual collectors have forged ahead of dealers, scholars, and other collectors to become trendsetters, the tastemakers. And this role, of enormous aesthetic and commercial importance, is one the Hajji Baba Club has, during its seventy-five years, played with profound impact. It has done so, as I hope the following pages will reveal, by simply remaining true to the goal established by its founders: “to promote the knowledge and appreciation of Oriental rugs as an art.”

1. THE FIRST HAJJI – ARTHUR URBANE DILLEY

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

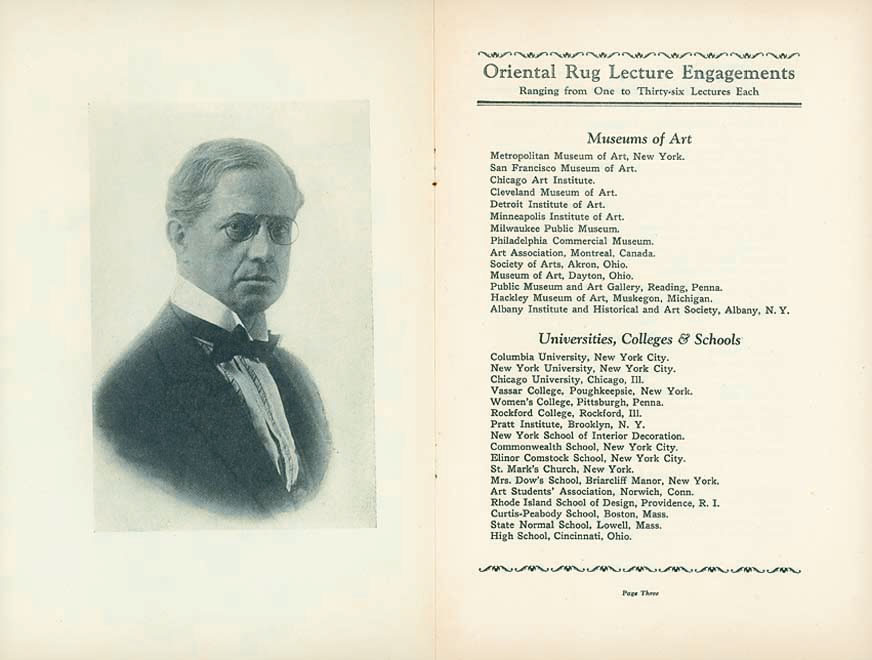

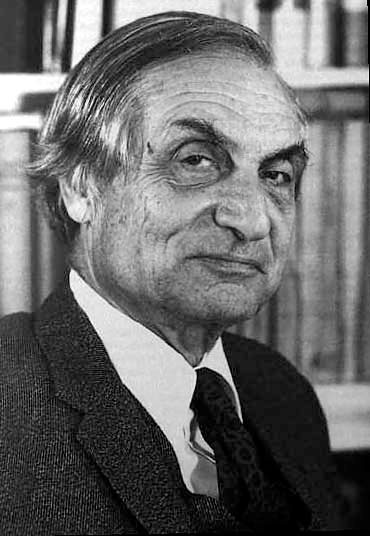

1.2 Arthur Urbane Dilley

1.2 Arthur Urbane Dilley

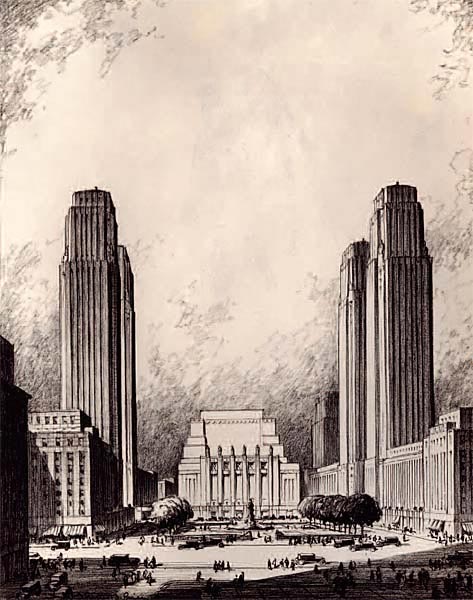

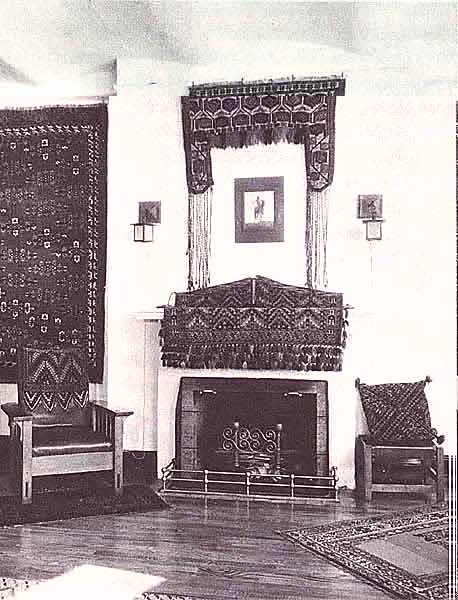

1.3 In 1932 Dilley’s rug gallery was located in The Architect’s Building, 101 Park Avenue, seen in this 1931 rendering by Morris & O’Connor, Architects.

1.3 In 1932 Dilley’s rug gallery was located in The Architect’s Building, 101 Park Avenue, seen in this 1931 rendering by Morris & O’Connor, Architects.

In 1903, good fortune, in the shape of a $10,000 inheritance, allowed Dilley to abandon the Taft School and to devote his full attention to Oriental rugs. He moved to Boston and opened a carpet store, a seemingly strange choice for a man who had anticipated making his living with his pen. But he failed to see the contradiction, because he planned to sell rugs in his own unique way, one that bore little resemblance to the methods used by his competitors.

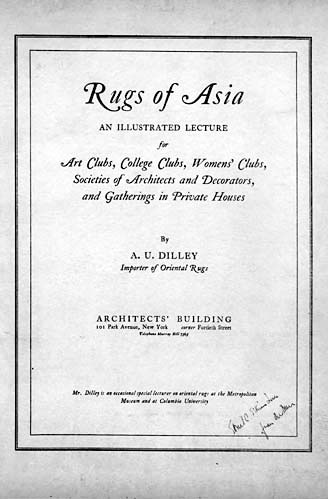

From the first, Dilley intended to find customers not by hawking rugs but by studying them and sharing what he learned with as many people as would listen to what he had to say, hoping all the while that some of those who listened would become his customers (fig. 1.4). He later described how he put his plan into operation: “Beginning in 1904, events moved fast. The august Boston Society of Architects needed a speaker at the annual dinner, and the art of Oriental rugs was the current topic of discussion.Would I oblige?… Whether the excellent wine, savory sauce, elegance of the art, or revelation of spoken word or a combination of these excesses was the motivating cause, the ovation that followed created a career. The result was fifty-seven lectures, quite unsolicited, within two years, before the Arts and Women’s Clubs of New England; and so great was public interest that twenty-two years later the Jordan-Marsh Company [a Boston department store] paid $2,500 for two weeks of lecture service,” all of which meant, as he, never one to underestimate his own accomplishments, described it, “a New England Renaissance of Oriental art.” 4

In 1908, Dilley’s shop was visited by a customer who would be as instrumental in shaping his career as were his well-attended lectures. The customer was James Franklin Ballard of St Louis, Missouri (fig. 1.5), a wealthy manufacturer and pitchman of patent medicines that could, according to his oft-repeated claims, cure any medical problem from psoriasis to cancer to the common cold.

On a visit to New York in 1905, Ballard happened to wander down Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue South) where a small Oriental rug in a dealer’s window captured his attention.

Although totally ignorant of rugs, he found this particular object intriguing. He entered the shop and asked about the rug and its price. When the dealer explained that he was asking $500 for it, Ballard declared such a figure to be absurd and walked out. But unable to stop thinking about it, he returned the next day and, after convincing the dealer to relent slightly in his price, bought the rug. That was the beginning. For the next twenty years, he acquired rugs at a furious pace, developing a collection that probably rivalled any private collection in the world, and, once satisfied with what he had gathered, began donating his rugs to his favourite museums: one hundred and twentysix went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (chosen because he believed more people would see his rugs there than at any other museum in the United States) in 1922 and, in 1930, another sixty-nine became the property of the City Art Museum of St Louis.

Ballard was Dilley’s best customer. But more important to his career, as well as to the history of the Hajji Baba Club, was his influence in convincing Dilley, in 1914, to move his business from Boston to New York, and in later persuading him to travel with his carpets and to lecture about them (fig. 1.4). Beginning at the Metropolitan Museum in 1919, they made stops at various museums across the country, a task for which Ballard compensated Dilley handsomely.

Once in New York, Dilley continued to do what he had done in Boston – buy and sell rugs, consult with collectors, and lecture. He maintained detailed records of his speaking engagements, listing them in various categories such as women’s clubs, museums, art clubs, and schools and colleges. The lectures were as much a source of pleasure and pride for him as they were a successful marketing tool.

During his Boston years, Dilley, who had maintained his literary ambitions despite his rug business, had written two books, really pamphlets, about rugs, How Oriental Rugs Are Sometimes Sold, which appeared in 1906, in which he sought to expose some of the deceitful techniques employed by unscrupulous dealers, techniques he asserted would disappear “only with the increase of the essential knowledge of rugs among buyers,”5 and in 1909, Oriental Rugs, a brief introduction to the subject which he hoped would provide some of that essential information.

1.4 (above & below) Three of the brochures Arthur Dilley

1.4 (above & below) Three of the brochures Arthur Dilley

used to promote his lectures on Oriental rugs.

2. THE FOUNDING FATHERS

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

1.5 James Franklin Ballard of St Louis.

1.5 James Franklin Ballard of St Louis.

1.6 Roy Winton

1.6 Roy Winton

It was his need to complete his magnum opus that had temporarily transformed Dilley into a recluse, that had caused him, even in 1932, to be slow to answer his door. When he did finally open it, two men were standing before him. “I am Roy Winton of the Amateur Cinema League,” explained the taller of the two. “This is my associate, Arthur Gale. We wish to congratulate you on the fine quality of Oriental Rugs and Carpets.” 6Roy Winton (fig. 1.6), a retired colonel in the United States Army, was then the managing director of the Amateur Cinema League, which one might mistake for an association encouraging home movies but which, in reality, was a band of serious, avantgarde film-makers who produced films that are, even today, deemed sufficiently notable to be regularly shown in museums, universities, and art theatres. Arthur Gale edited Movie Makers, the magazine published by the Amateur Film League, and as serious a magazine as the League was an association.

1.7 Arthur Arwine’s apartment was on the fourth floor of One Sheridan Square,

1.7 Arthur Arwine’s apartment was on the fourth floor of One Sheridan Square,

the building depicted in the centre ofthis etching by Paul Berdanier.

Dilley suggested that Winton and Gale might enjoy meeting Anton Lau (fig. 1.8). Known as Tony to his friends, Lau was a consulting engineer from nearby Bloomfield, New Jersey, an individual with an avid interest in Near and Far Eastern art as well as an impressive collection of Oriental arms and armour. When Dilley spoke to Lau about arranging a meeting of the four men, Lau reminded him of another who might want to join them, a man Lau had met casually at meetings of the New York Architectural League, but who shared his and Dilley’s zeal for Eastern art, Arthur Arwine (fig. 1.9).

Arwine, like Lau, was an engineer. In 1910, with the help of Harry Pray Wooster of Tiffany Studios, which at the

in a variety of sizes (fig. 1.10).

1.8 Anton (Tony) Lau

1.8 Anton (Tony) Lau

1.9 Arthur Arwine

1.9 Arthur Arwine

His unique apartment attracted attention; in 1929 an interior design magazine asked to photograph it for an upcoming article. But when the stock market crash set the design business back on its heels, the magazine’s editors gave up their plan, although, at Wooster’s urging, they did agree to allow Tiffany’s to display the Arwine photographs in the windows of its Madison Avenue gallery. It was there that Lau happened upon the apartment pictures and realised that he knew, albeit casually, the person who had created such an intriguing residence. Lau informed Dilley of his discovery, invited him to examine the photographs and, at Dilley’s urging, called Arwine to ask whether the two of them could see the apartment. The first words out of Dilley’s mouth as he walked into Arwine’s home were, according to his host, “Well, we haven’t been sent on a wild goose chase.”7 The visitors stayed for several hours and, before leaving, asked if they might return.

On their next visit, Dilley and Lau brought Winton and Gale with them and spent a Saturday afternoon examining and discussing Arwine’s collection in particular and rugs in general. The five men continued their Saturday meetings, but as often as they met, they never seemed to exhaust their favourite subject. Soon they decided to meet for lunch before going to either Arwine’s or, from time to time, to Winton and Gale’s where they would talk rugs until dinner, break to eat together, and return for more of the same during the evening.

Dilley wrote about these gatherings in ‘Group Portrait of Club Founders and the Times in Which They Lived’: “Pleasant memories are portraits one would wish never to forget: Arwine’s splendid collection of Turkoman rugs which to him filled the void of wife and child… Lau collecting rug data, both fact and fancy, scrapbook fashion, as if to compile an encyclopedia. The eagerness of Winton and Gale to solve the thousand riddles of nomenclature, as if knowing a name determined the difference between knowledge and ignorance, appreciation and indifference. They knew it to be only the first step. Finally long before my acquaintance with these splendid men, my own unconquerable will to write my own version of rugs from the notes of many lectures, my office door unlocked against business intrusion. No mutual admiration society ever existed that eclipsed the fervor of this one.” 8

By Arwine’s account, Gale was the first to suggest the five men establish a more formal organisation. On July 9, 1932, they gathered at the home of Tony Lau in New Jersey, created the Club, and elected officers. Not surprisingly Dilley was chosen as the group’s first president, Roy Winton its vice-president, and Tony Lau its secretary and treasurer. Although a club of only five members, the founders anticipated others would be quick to join, because the Club’s constitution, drafted by Lau and Gale, called for a nine-member board of directors. The same document also stipulated that only males were eligible for membership, a provision added after Arthur Gale argued passionately that women did not “have the correct attitude towards Oriental rugs.”9

Selecting a name proved to be considerably more complicated. Originally it was to be The Oriental Club of New York, but Dilley thought that entirely too pedestrian. As he described the sequence of events: “The name to adopt presents a difficulty. Obviously to avoid being commonplace and unrealistic, it should be Asiatic. When the new president suggests Hajji Baba, the assembled savants, never having heard of him, inquire as to his ancestry and credentials…‘He is the hero of James Morier’s novel, Hajji Baba,’ says the President… Again, literally translated, the name means Pilgrim Father, which is our destiny as founder of this Club.”

One can be reasonably certain that Dilley, rarely a man of few words, provided a lengthier explanation of his choice of name. In all probability, he described the British diplomat and writer James Justinian Morier’s 1824 picaresque novel in detail, outlining the events that took Hajji Baba from Esfahan, where he had been born the son of a barber, through a variety of trials and careers until ultimately he became an indispensable assistant to the British ambassador to Persia. Dilley was especially fond of Hajji Baba because, “He too was a rogue, never paying for what he coveted more than ten cents on the dollar. In that respect he is our patron saint…”,10 not a bad example for anyone collecting rugs during a depression.

1.10 Arthur Arwine’s apartment at One Sheridan Square,

1.10 Arthur Arwine’s apartment at One Sheridan Square,

bedecked with Turkmen tribal carpets and other weavings.

Once the question of name had been settled, the time had arrived for the newly-elected president to deliver his acceptance speech. Dilley, thoroughly convinced that prolixity was a virtue, delivered an address to the assembled group, all four of them, that lasted, according to the Club’s archives, “for a period of sixty-two minutes” which, at its conclusion, again according to the archives, was received “with loud applause and great acclaim; it required the unremitting efforts of the full membership which constituted itself as a Sergeant-at Arms-at-Large to restore order.” 11

While one cannot say with any certainty that Dilley’s address was filled with references to the declining interest in, and prices of, Oriental carpets that followed the stock market crash in 1929, his propensity to dwell on that theme makes it hard to believe he totally ignored the subject during those sixty-two minutes. Perhaps his obsession with the topic made the discouraging sales of his book easier to accept, or perhaps he was prescient enough actually to anticipate that the wild enthusiasm for rugs that had existed during the 1920s was beginning to wane, and would continue to do so over the course of the Depression, eventually reaching such a low ebb during the Second World War that more than two decades would pass before the recovery would begin.

But if 1932 was the worst of times for rugs, as it certainly was for dealers, it was also the best of times, clearly so, for collectors. As Dilley admitted, “During the Club’s early

years (1932-1942), the rug market still contained a sufficient numberof antique rugs, conjoined with a blissful ignorance of them, to make hunting the rarest a thrilling experience.”12 Not only were significant rugs available, especially in New York, but they were available from dealers who normally sold only new rugs and were thus unaware of the importance of certain old ones. Furthermore such rugs were selling for absurdly low prices. What collector would complain of such a world? Rock-bottom prices were the result of the Depression: the extraordinary availability of important rugs in the Hajjis’ backyard, New York City, while less easily explained, was also no accident.

New York had, during the years before World War I, developed into the art centre not only of the United States but of the world, a situation that only became more and more obvious during the 1920s. The late nineteenth century had seen an unprecedented accumulation of wealth in private hands. American ‘squillionaires’, as Bernard Berenson labelled them, had made fortunes in iron and steel, in railroads and traction, and in mining. Many of the individuals who accumulated this wealth – the Astors, Vanderbilts, Whitneys, and Belmonts – were long-time residents of New York, but others had arrived more recently after making their money elsewhere.

1.11 The entrance hall of Mr & Mrs George Blumenthal’s New York residence,

1.11 The entrance hall of Mr & Mrs George Blumenthal’s New York residence,

with architectural details and furnishings taken from various palaces in Europe.

3. MOGULS AND MERCHANTS – A NEW YORK TRADITION

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

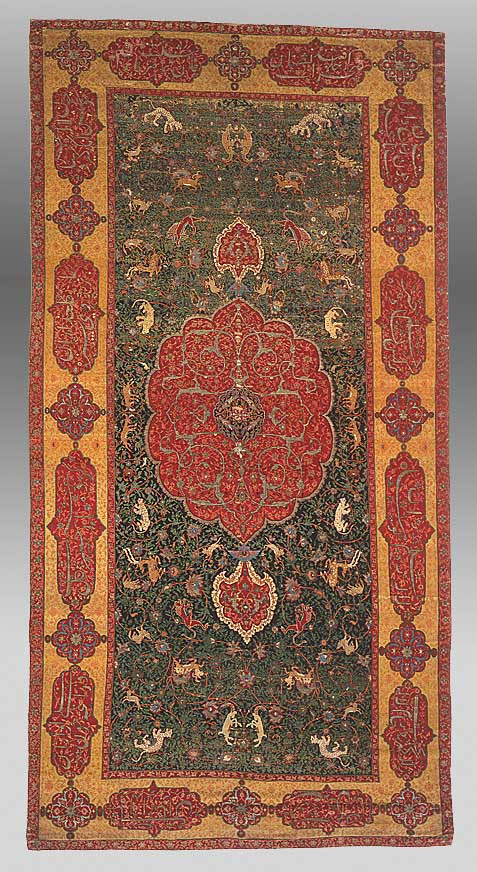

New York had an irresistible attraction for tycoons. Charles T. Yerkes, the builder of Chicago’s transit system, gave up South Lake Shore Drive in Chicago for Fifth Avenue (fig. 1.12). The steel magnate Judge Elbert Gary, like Yerkes, abandoned his luxurious Chicago home for an even grander Fifth Avenue mansion. Senator William A. Clark arrived from Montana, where he had made his millions in mining and built a home so enormous and so improbably conceived that it boggled even the minds of other tycoons. In 1906 Henry Clay Frick left Homewood Avenue in Pittsburgh to join the other wealthy folk already on Fifth Avenue. Even John Pierpont Morgan, who arrived earlier and consequently lived further downtown, had also come from out of town, though only from nearby Hartford, Connecticut. For the super wealthy, a New York residence was at least as necessary as two or three dozen servants.

On the heels of the tycoons came a variety of businesses that catered to their insatiable appetites for goods and services. Among them were art dealers, some of whom

arrived knowing exactly how to catch the eye of the moguls on Fifth Avenue. Stanford White, New York’s leading

interior decorator as well as its leading architect at the turn of the century, was probably among the first to understand that the extraordinarily wealthy saw themselves, by virtue of their gigantic fortunes, as a new element in American society, an aristocracy separate and distinct from the rest of the population, even from the professional and well-to-do classes.

To confirm their place, they sought to surround themselves with the accoutrements of aristocracy, with dwellings that mimicked the residences of European nobility, with European antiquities, furniture bearing the names of French kings, paintings and sculptures that had, since their creation, resided in the homes of royalty and nobility, as well as carpets that might, centuries earlier, have been presented to their original owners as gifts from a Safavid Shah or an Ottoman Sultan (fig. 1.11). The result, as Wesley Towner described it: “Art collecting, the ultimate luxury, proof than a man could afford the utterly inutile, came into vogue with the virulence of an epidemic.”13

1.12 The drawing room in the Fifth Avenue residence of Charles T. Yerkes, showing

1.12 The drawing room in the Fifth Avenue residence of Charles T. Yerkes, showing

his ‘Sanguszko’ Safavid medallion carpet – now in the Tehran Carpet Museum.

Dealers – or antiquarians as those of that generation preferred to be called – flocked to New York from all over Europe and the Middle East. Henry J. Duveen came from London to establish a foothold for Duveen Brothers, but he was certainly not the first. Durand-Ruel and Gimpel & Wildenstein arrived from Paris, but only after Knoedler & Company had already opened its doors. Jacques Seligmann also came from Paris. It was his son, Germain Seligman – he preferred to spell his last name with only one ‘n’ – who described his American customers as individuals who “had every kind of instinct but aesthetic.”14 From Istanbul by way of Paris came the Armenians Hagop Kevorkian and Dikran Khan Kelekian (figs. 1.13, 1.14), specialists in Islamic art. These recent arrivals knew, because of their connections overseas, that they could easily compete with the likes of Stanford White and other New York dealers who were themselves busy ransacking European collections to satisfy the desires of customers.

Auctioneers were equally aware of the opportunities in New York. Thomas E. Kirby, who would head the American Art Association, the premier auction house in the United States for more than four decades, began his career in Philadelphia before making the move to New York in 1876, prompted by his realisation that selling art in New York provided the surest route to financial success. Hiram Haney Parke, one day to be a partner in Parke-Bernet, the house that dominated

the auction business after the decline of the A.A.A, also made the move from Philadelphia, where he had previously occupied the podium at the Samuel T. Freeman Company.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, one had to go no further than New York, a city with an apparently unending hunger for antiquities and with a multitude of ‘antiquarians’ trying to satisfy those cravings, to locate any manner of treasure that anyone might desire. From paintings and sculpture to furnishings and carpets, it was all readily available, albeit at prices that were, of course, beyond the imaginations of most New Yorkers.

When America’s millionaires went shopping for carpets, they wanted the kind of carpets that graced the homes of Europe’s aristocrats – Safavid Persian, Mughal Indian, and Persian-like Ottoman Turkish carpets. In addition to having been sanctioned by virtue of having come from Europe’s grandest homes, these carpets also enjoyed the endorsement of high-end dealers such as Duveen and Kelekian. Anyone who might doubt that these were, without question, the most thoroughly desirable of all Islamic carpets, an absolutely essential element in any home of distinction, would have had those doubts put to rest merely by reading the New York newspapers.

1.13 The Armenian antiquarian Dikran Khan Kelekian

1.13 The Armenian antiquarian Dikran Khan Kelekian

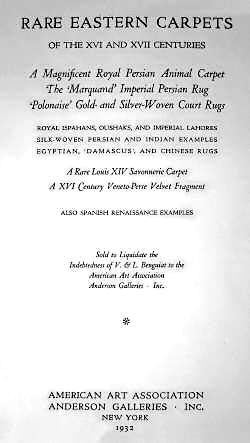

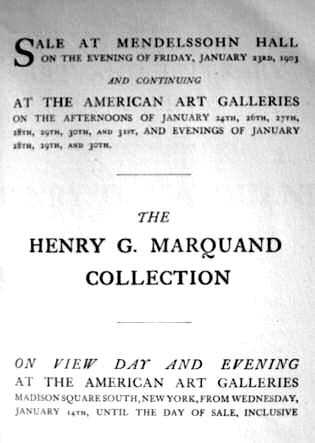

In 1903, the American Art Association, with great fanfare, sold the mammoth art collection of Henry G. Marquand, former president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 1.15). It required eleven days to disperse, and included 47 carpets, the first of real importance to be sold at auction in the United States, all of them pieces that Duveen would have been happy to handle. The press gave the Marquand sale the sort of attention they normally devoted to nothing less than an off-year election or one of Teddy Roosevelt’s trust-busting campaigns. In 1910, the Charles T. Yerkes Collection, perhaps the finest private holdings of carpets in the world at the time, went under the hammer (fig. 1.16). Thanks to the notoriety that surrounded Yerkes’ name, it attracted even more attention than the Marquand sale. The same year, the MetropolitanMuseum unveiled its first exhibition of carpets, a breathtaking show curated by Bode’s former student, William R. Valentiner. In each of these instances, the carpets featured were Persian or Persian-like.

The First World War temporarily displaced carpets from the pages of the newspapers, but during the 1920s carpets again became big news and remained so right up to the point when the Hajji Baba Club was formed. Reporters were there in 1922 when James F. Ballard donated 126 rugs to the Metropolitan Museum, the first significant donation of carpets

since J.P. Morgan, Benjamin Altman, and Isaac Fletcher had, prior to the war, contributed their masterworks. Major auctions of carpets still occurred regularly, and newspaper readers scrambled to learn how high prices might go at those sales.

Few such auctions attracted more press attention than the five that sold the carpets of Vitall Benguiat (fig. 1.18). To speak of “the carpets of Vitall Benguiat” is less than accurate, because, although discovered and purchased by him, they were rarely his property. The A.A.A. provided the funds he used to buy whatever he bought, retained whatever money the Benguiat sales generated until Vitall came looking for another loan to buy more rugs, and actually owned the carpets. Had one encountered Benguiat in his ‘office’, a table at Child’s, an unimpressive restaurant at Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, one might have wondered why a dealer of such renown operated from such humble quarters, but his flamboyance would have quickly overwhelmed the reality that he was almost always broke. His office, like his legendary gluttony, would seem just another aspect of a persona that made him a favourite of reporters. Although the William A. Clark sale in 1925 and, specially, the Elbert Gary sale in 1928 (fig. 1.17), were reported in great detail, the combination of Benguiat sales produced vastly more column inches than either of them.

1.14 Dikran Kelekian’s New York gallery, 1898

1.14 Dikran Kelekian’s New York gallery, 1898

them John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, owned more of almost anything they might want and were no longer in a buying mood. Benguiat was all too well aware of the trend, but the public remained blissfully ignorant.

Meanwhile, during the years before 1932, a series of carpet exhibitions kept masterpiece carpets in the spotlight. Although held in Philadelphia, the 1925 ‘Exhibition of Persian Art’, organised by Arthur Upham Pope (fig. 1.20) and his wife, Phyllis Ackerman (fig. 1.21), attracted considerable attention in New York. Among the many New Yorkers who travelled to Philadelphia to see what Pope and Ackerman had assembled were Mrs John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and her friend Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, both of whom owned spectacular carpets. Pope organised another exhibition the following year at the Art Club in Chicago. It too drew visitors from New York. Finally, in 1930, Manhattanites had a show of their own; Maurice Dimand, who would shortly become a Hajji, gathered several of the best ‘Polonaise’ rugs in the United States for a display at the Metropolitan.

1.15 Catalogue of the 1903 Henry G. Marquand sale

1.15 Catalogue of the 1903 Henry G. Marquand sale

1.17 Catalogue of the 1927Judge Elbert H. Gary sale

1.17 Catalogue of the 1927Judge Elbert H. Gary sale

1.18 Catalogue of the 1932 V. & L. Benguiat sale

1.18 Catalogue of the 1932 V. & L. Benguiat sale

4. DEMOTIC DEVOLUTION – MYTH AND MYSTERY

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

All the attention given to Classical carpets and their high prices had, as if by osmosis, awakened interest in rugs that dealers such as Duveen disparaged as examples of the degeneration of a once proud art form. Intensifying this enthusiasm were two extremely popular rugs books, Mumford’s Oriental Rugs, which has already been mentioned, and Walter A. Hawley’s Oriental Rugs, Antique and Modern, originally published in 1913, but reprinted twice during the 1920s. Both described rugs in such extravagant terms that Dilley felt compelled to comment: “Even Thoreau [who Dilley considered to be the ultimate ascetic], subjected to similar influence, would have succumbed at least to the literature of the art that made resplendent the courts of Babylon, Baghdad, Persepolis, and Ctesiphon; Cambaluc, Samarkand, Cairo, and Damascus; Shapoor, Tabriz, Kasvin, and Ispahan; Ghazni, Agra, Constantinople.”16 As wealth became more widely distributed during the 1920s, more and more people found themselves able to mimic the tastes of the super rich, able, for example, to purchase a nineteenth-century Caucasian rug which, to the untrained eye, looked more-or-less like one that might be found in the home of a Rockefeller or a Havemeyer.

Fortunately for those in the market for rugs, the political turmoil of the early twentieth century and World War I conspired to make affordable rugs available in the United States in greater numbers than ever before, and New York, not surprisingly, became the hub of this commercial activity.

In fact, even before the outbreak of war in 1914, New York saw more retail rug sales each year than any other city in the world, a situation partially explained by the arrival in the United States, between 1890 and 1914, of approximately 66,000 Armenian immigrants, forced to flee Turkey in the face of persecution there. For some of these new arrivals, the business that came most naturally was the rug business. By 1914, some seventy per cent of the American market in Oriental rugs was controlled by Armenians, and in New York City alone, where most of these newcomers first stepped onto American soil, 75 rug stores were Armenian-owned.

No New York dealer, Armenian or otherwise, had to contend with a shortage of merchandise. Many rugs, most of them from Turkey and the Caucasus, arrived with the immigrants, but as those initial inventories began to shrink, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire meant another influx of goods, soon followed by even more from the Caucasus and Central Asia, rugs displaced by the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War. In 1890, the total value of Oriental rugs imported into the United States was $135,000. By 1907 that figure had increased to $4,000,000 and by 1924 to nearly $8,000,000.

1.19 The Safavid Persian medallion carpet that had once belonged to Henry G. Marquand was incorrectly reported to have been sold at auction in the early 1930s, just before the foundation of the Hajji Baba Club, to the New York dealer Parish Watson for $100,000. Not long afterwards it was sold by Mitchell Samuel of the New York dealers French & Co. to Mrs John D. McIlhenny, who bequeathed it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in memory of John D. McIlhenny, Jr., no. 43.28.1.

1.19 The Safavid Persian medallion carpet that had once belonged to Henry G. Marquand was incorrectly reported to have been sold at auction in the early 1930s, just before the foundation of the Hajji Baba Club, to the New York dealer Parish Watson for $100,000. Not long afterwards it was sold by Mitchell Samuel of the New York dealers French & Co. to Mrs John D. McIlhenny, who bequeathed it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in memory of John D. McIlhenny, Jr., no. 43.28.1.

Initially, selling rugs to an American public that had, with few exceptions, no experience of them, proved a problem. Convinced that Axminster and Wilton carpets were perfectly adequate floor coverings, Americans were slow to convert to the new and strange alternatives. So perplexing was the problem that in 1899 Mumford wrote an article for Harper’s Bazaar entitled, ‘The Problem of Oriental Rugs’, in which he described the difficulties dealers faced in attempting to interest an uninformed and reluctant clientele in these products.

Eventually the dealers themselves developed a strategy that helped to solve the problem. In addition to describing Oriental rugs as durable enough to withstand several generations of abuse, and promising that, unlike Axminsters and Wiltons, they would undoubtedly appreciate in value, they also began to surround rugs with mystery, to elaborate on their exotic nature and on the exotic nature of those who made them, to portray them as objects that represented cultural distance. Dealers selling affordable rugs taught themselves to function not only as rug merchants but also as purveyors of rug lore, much of it totally fashioned out of whole cloth. A dealer who could spin a first-class tale about his rugs in terms of “the veil of enchantment that hangs over the mystic symbolism of their design,”17 or by discussing “the nature of the exotic people who weave them,”18 might convince a customer at least to take a rug on approval.

1.20 Persian art exhibition organiser Arthur Upham Pope, who became a Hajji in 1935

1.20 Persian art exhibition organiser Arthur Upham Pope, who became a Hajji in 1935

hand, many individuals – like three of the Club’s founders, Winton, Gale, and Arwine – in trying to understand rug designs and their creators, often, as their investigations

intensified, became less and less tolerant of those qualities Bode and Riegl were willing to abide – Western influences and rugs made for Western markets. These new enthusiasts began demanding authenticity in their rugs, a quality found only in rugs woven by people using their own traditional methods to fashion products totally untainted by outside influences and intended strictly for their own use, not some distant consumer’s.

5. THE CLUB’S EARLY YEARS – 1932 TO 1941

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

1.22 Joseph V. McMullan

1.22 Joseph V. McMullan

1.25 W. Parsons Todd.

1.25 W. Parsons Todd.

that enthusiasm, but it would take another World War to put it down for the count. For those who had become excited about carpets during the 1920s, who had the good fortune to live in or near New York City, where more dealers and a better selection of carpets were to be found than in any other Western city, and who managed to remain solvent during difficult times, the 1930s was not as Dilley described it, the worst of times for carpet collectors; in most respects it was the best of times, certainly

an ideal time to assemble a collection or perhaps even to organise a rug club and hope to attract members.

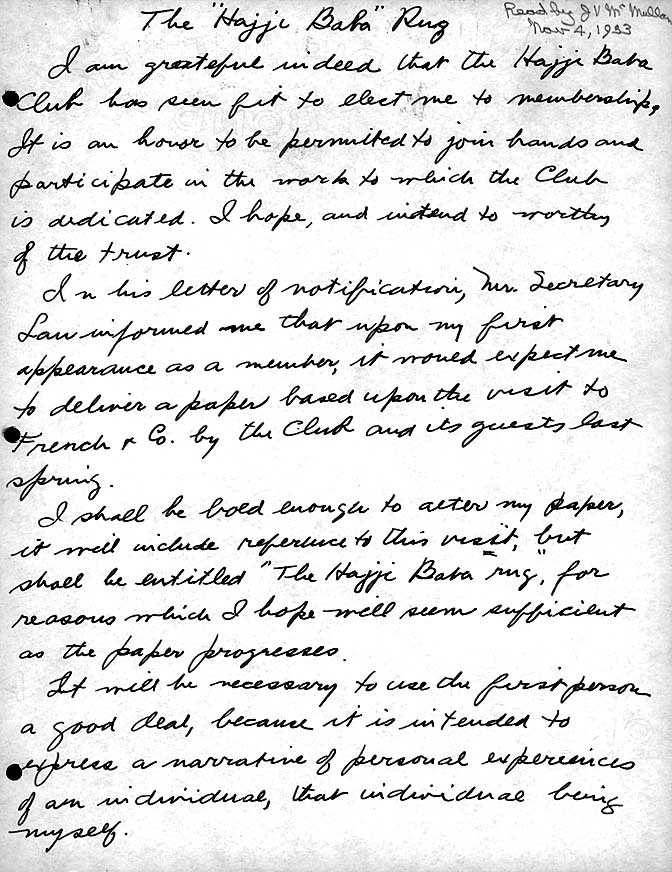

1.23 The first page of Joseph McMullan’s 4th November 1933 presentation to the Hajji Baba Club

1.23 The first page of Joseph McMullan’s 4th November 1933 presentation to the Hajji Baba Club

consistently placed demands on its students that only the brightest and most industrious can meet. Hardly a handicap. McMullan knew how to gather and organise information as well as anyone. He began his research in the Art Room of the New York Public Library before movingon to the carpets on display at the Metropolitan Museum and then to the auction rooms of the American Art Association, where

he could handle the rugs and where, from his point of view, there existed “the best art show in town.” At the same time he was buying and studying any rug book he could find. He was also buying the occasional rug but, because he knew no one who shared his interest, was, in his words, “playing a lone hand.”20

On a visit to B. Altman’s, another New York department store, he saw a pair of fragments that intrigued him but which neither he nor the salesman recognised. “On a subsequent visit to Altman’s, to look at a room-sized rug, I mentioned these fragments to another salesman. He dug one up, the other had gone. I bought the other one blind.” Although this second salesman also knew nothing about McMullan’s fragment, he did provide McMullan with the name of the purchaser of the missing piece. He was Roy Winton. Using the City Directory, McMullan tracked him down and, never one to be denied, barged in on Winton and Gale in the middle of dinner. “About 2 a.m. the following morning, I left the Gale-Winton apartment, with a whole new world to look at

1.26 Hajjis visiting Philadelphia in either 1937 or 1940:

1.26 Hajjis visiting Philadelphia in either 1937 or 1940:

Left to right: Arthur Gale, an unidentified member, Joe McMullan,

an unidentified member, Arthur Dilley, Tony Lau, Theron Damon,

Robert Peckham, Fred Kramer, and Parsons Todd

Winton invited McMullan to attend the May 6, 1933 meeting of the Hajji Baba Club. The proprietor of French & Company, Mitchell Samuels, one of New York’s premier dealers, had invited the Hajjis to examine his inventory. “The experience was a notable one,” McMullan later said. “I had viewed the finest at the Metropolitan Museum, but always alone. Here was something different… What a contrast to the solo visits.” He became a Hajji at the Club’s next meeting, on June 10, 1933, and at the one that followed presented a paper (fig. 1.23) which began with these words: “It is an honor to be permitted to join hands and participate in the work to which the Club is dedicated. I hope, and intend, to be worthy of the trust.”22 For his next forty years as a Hajji, he did indeed prove worthy.

The following year, 1934, saw several other illustrious figures join the ranks of the Hajji Baba Club. Among them were Maurice Dimand, who would become curator of Islamic Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; W. Parsons Todd (fig. 1.25), who later, in 1950, donated his his art collection and his home, Macculloch Hall, to the city of Morristown, New Jersey; and Theron Damon, formerly a resident of Turkey for twentyfive years, who was probably

McMullan’s closest friend in the Club, his regular companion at auctions, and the person who joined the Club knowing more about rugs than any other member except Dilley.

Several Hajjis first learned about the Club while attending a Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.) sponsored adult education class on rugs taught by Krikor Krikorian at LeRoy High School in Greenwich Village. McMullan and Olivet had both taken Krikorian’s class. So too did Alvin Pearson, Ovid Whelchel, George Clewell, and Newton Foster. These and the other early Hajjis collected a variety of rugs. Dilley, who vetted his colleagues’ rugs, reserved his highest praise for the collections of McMullan, Olivet, Damon, and Oliver Brantley who, because he operated an important rug cleaning business in Brooklyn, should have known a good rug from a bad one. Dilley stated that the Hajjis (fig. 1.26) collected village and nomadic rugs from Central Asia, Turkey, and the Caucasus and that they were largely uninterested in kilims, Chinese rugs, Baluch rugs – for which most of the group had no respect – and Persian tribal rugs, Persian ‘town’ rugs having earned a bad reputation because of the dismal quality of many modern examples.

1.27 A Tekke Turkmen bride’s rug, once owned by Amos B. Thacher,

1.27 A Tekke Turkmen bride’s rug, once owned by Amos B. Thacher,

published as pl. 23 in his 1940 book, Turkoman Rugs. Private collection, Hamburg

He also claimed the Hajjis had little interest in the Ghiordes or Kula prayer rugs that had been immensely popular during the 1920s and which Dilley enjoyed disparaging. By and large, the rugs the Hajjis were buying were rugs many connoisseurs, such as exhibition organisers Pope and Ackerman and dealers Kelekian or Duveen, still, even in the 1930s, considered uncollectable. But most Hajjis, lacking the resources to buy from Kelekian or Duveen, were blazing their own trail, a new one.

This does not mean that a Hajji might not occasionally come across and purchase a rug that any top-flight dealer would have been delighted to own. Such purchases usually

resulted from the inability of a dealer who normally handled newer rugs to recognise the value of a particular ancient one. As Dilley explained, “Seldom was there a meeting of the group that failed to produce an atomic-rug explosion [a member’s presentation of a great antique rug]. Moreover, the detonators had sufficient understanding of the art to produce proof of assertions and consequently to speak with authority. When Olivet and McMullan, [Amos] Thacher and Brantley were discovered and inducted, and Pope [Arthur Upham Pope became a Hajji in 1935] with mighty stroke raised the

speed of the boat – headed into Duveen wharf – the crew was competent,”23 by which I think he meant the Hajjis, because they knew what they were doing, were finding rugs that Duveen would envy.

In the midst of mixing his metaphors, Dilley did make an important point. The Hajjis could, at an early date, speak with considerable authority about rugs. From the beginning, they understood that collecting meant more than just accumulating rugs for pleasure; it meant gathering them knowledgeably. Interviewing Hajjis in preparation for his article in the New Yorker on September 2, 1939, Richard O. Boyer heard Club members articulate this point: “The Hajji Babas declare they are the world’s premier rug collectors, not because they own the rarest pieces but because they know more about Oriental rugs than any other group in the world. Their knowledge, they say, enables them to enjoy Oriental masterpieces with a depth of appreciation totally beyond those who merely own them.” With the exception of Maurice Dimand and later John Shapley, the early Hajjis were not art historians, but they brought to their subject an enthusiasm that in large degree compensated for their lack of formal training.

1.28 Amos Bateman Thacher

1.28 Amos Bateman Thacher

1.29 Frederick Moore

1.29 Frederick Moore

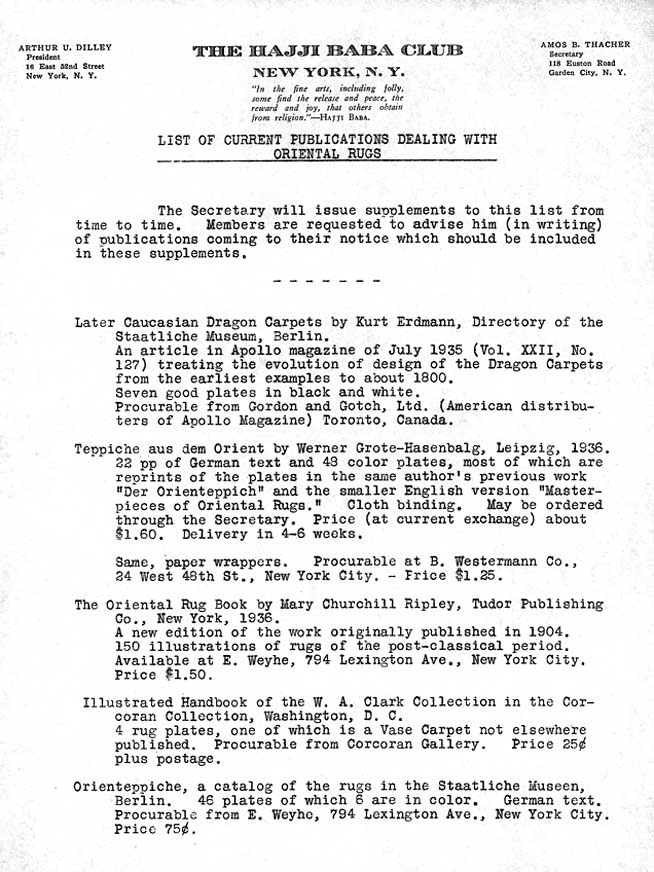

1.30 Arthur Dilley’s ‘List of Current Publications Dealing with Oriental Rugs’, which in this version included information supplied by Ovid Whelchel about where the books could be purchased.

1.30 Arthur Dilley’s ‘List of Current Publications Dealing with Oriental Rugs’, which in this version included information supplied by Ovid Whelchel about where the books could be purchased.

1.31 Joseph E. Widener

1.31 Joseph E. Widener

1.32 The Textile Museum

1.32 The Textile Museum

in George Hewitt Myers’ house at 2320 S Street, Washington, D.C.

1.33 Textile Museum founder George Hewitt Myers

1.33 Textile Museum founder George Hewitt Myers

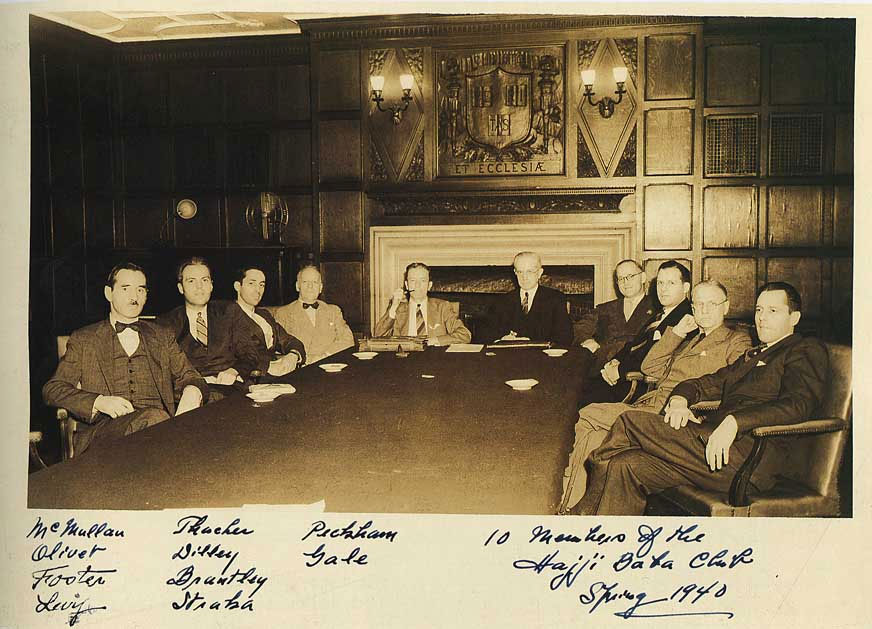

1.34 Members of the Hajji Baba Club, Spring 1940.

1.34 Members of the Hajji Baba Club, Spring 1940.

Left to right: Joseph McMullan, Harold Olivet, Newton Foster, Julian Levy, Amos Thacher, Arthur Dilley, Oliver Brantley, Jerome Straka, RobertPeckham, and Arthur Gale.

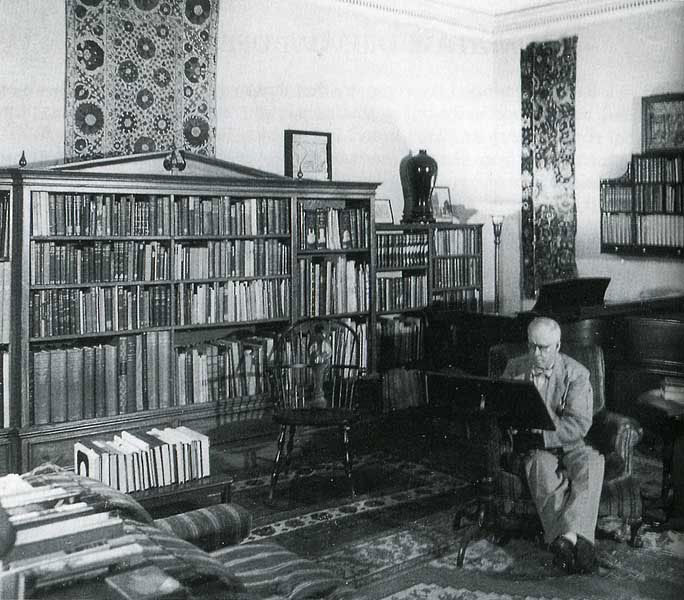

1.35 The Library at the Harvard Club where the Hajjis’ ‘show and-tell’ sessions took place

1.35 The Library at the Harvard Club where the Hajjis’ ‘show and-tell’ sessions took place

1.36 Arthur Upham Pope in his office at the American Institute for Persian Art and Archeology

1.36 Arthur Upham Pope in his office at the American Institute for Persian Art and Archeology

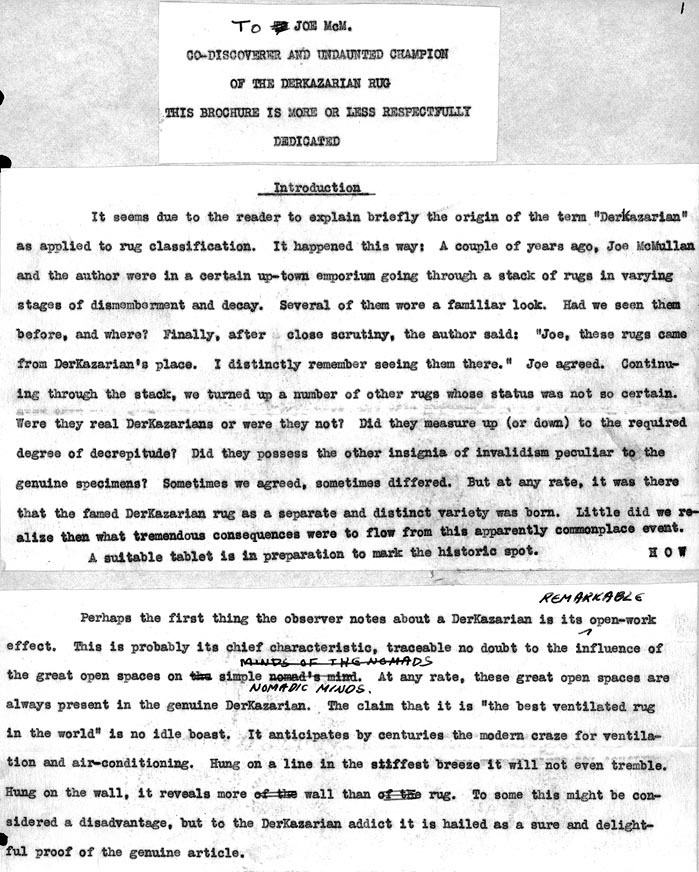

1.37 The first page of Harold Weaver’s ‘Derkazarian Rugs’ lecture to the Club

1.37 The first page of Harold Weaver’s ‘Derkazarian Rugs’ lecture to the Club

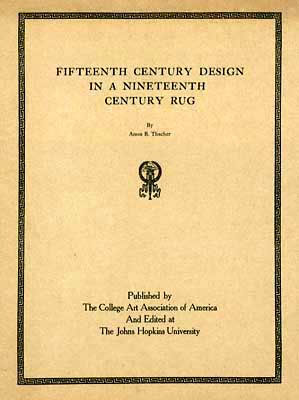

1.38 Amos Thacher’s 1939 paper ‘A Fifteenth Century Design

1.38 Amos Thacher’s 1939 paper ‘A Fifteenth Century Design

in a Nineteenth Century Rug’ published in The Art Bulletin.

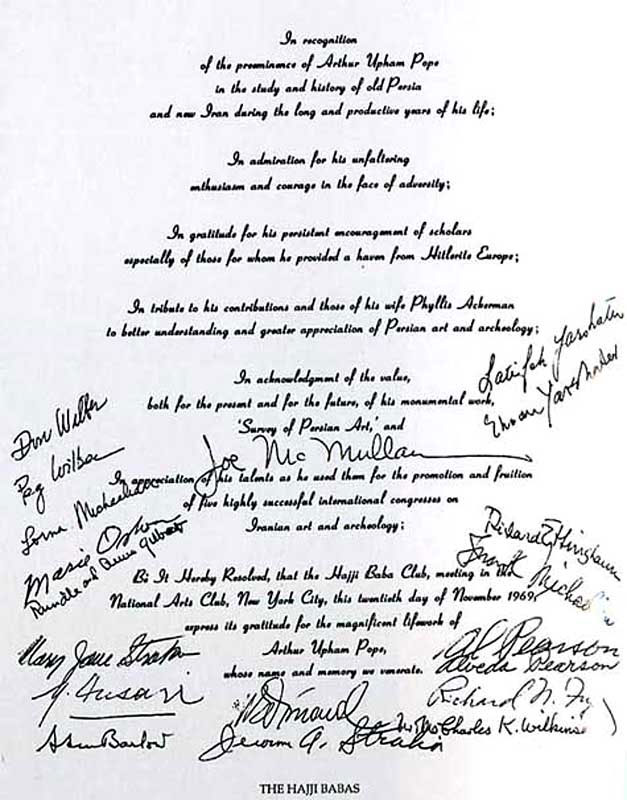

1.39 Arthur Upham Pope’s certificate of recognition from the Hajji Baba Club

1.39 Arthur Upham Pope’s certificate of recognition from the Hajji Baba Club

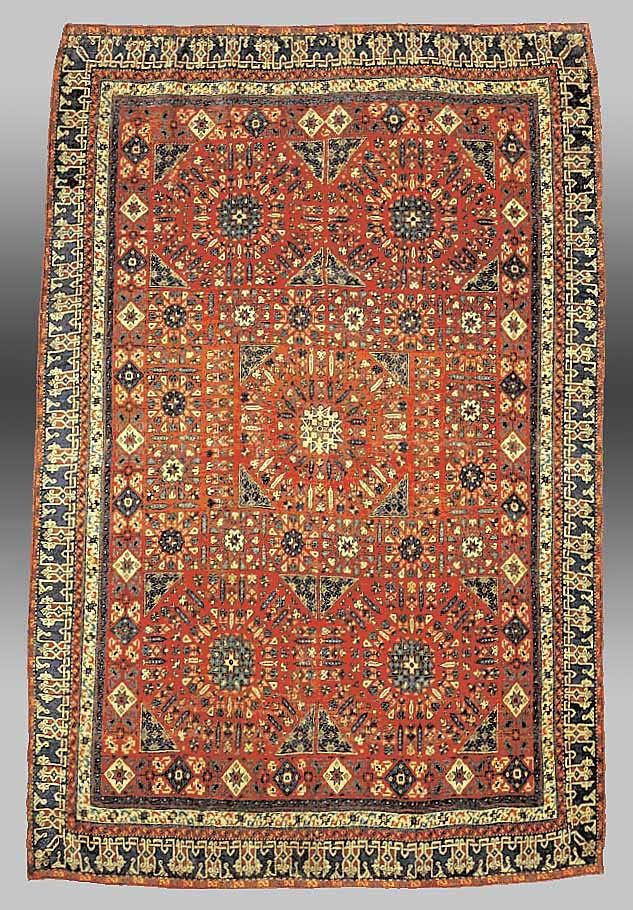

1.40 Caucasian Dragon Carpet,shown to the Club at the September 1936 meeting.

1.40 Caucasian Dragon Carpet,shown to the Club at the September 1936 meeting.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Joseph V. McMullan, no. 1974.149.5

1.41 H. McCoy Jones

1.41 H. McCoy Jones

6. WAR, PEACE AND PROSPERITY – 1942 TO 1959

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

1.43 The National Arts Club, venue for Hajji Baba Club meetings since 1959

1.43 The National Arts Club, venue for Hajji Baba Club meetings since 1959

Washington, D.C., not only authored exhibition catalogues on Turkish, Turkmen and Afghan rugs, but later donated his collection of some six hundred tribal and nomad rugs to the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco.

A meeting place for the Club became a problem during the post-war period. After the good years at the Harvard Club and then several years of sporadic meetings flitting between various clubs, restaurants or carpet galleries – most regularly Karekin Beshir’s – the members decided in 1958 that consistently meeting at one location was a necessity if the Club was to prosper. The following year, after considering various possibilities, they enthusiastically endorsed the National Arts Club (fig. 1.43), a Gramercy Park landmark, housed in a nineteenth-century building the architect Philip Johnson described as “one of the most magnificent in New York.” It had been the home of Samuel J. Tilden, former Governor of New York and Democratic Party candidate for President. Except for a brief interruption during the 1970s, it has been home to the Club ever since.

1. 44 Arthur Dilley regales members at the 1954 Hajji Baba Summer Picnic

1. 44 Arthur Dilley regales members at the 1954 Hajji Baba Summer Picnic

One would be hard pressed to imagine a more suitable base for the Hajjis than the National Arts Club, the ideal setting for the distinguished array of speakers who have addressed the Club. Professor Philip Hitti of Princeton was among the first to speak there, his topic ‘Rugs and the History of the Middle East’. His place at the lectern has, since 1959, been taken by an all-star cast, including Richard Ettinghausen of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts; Oleg Grabar, then from Harvard; Ernst Kühnel and Kurt Erdmann from the Islamic Department of the Berlin Museum; Maurice Dimand, Ernst Grube, Daniel Walker and Stefano Carboni of the Metropolitan Museum; Layla Diba and Aimeé Froom of the Brooklyn Museum; Louise Mackie, then with the Royal Ontario Museum; Walter Denny of the University of Massachusetts; Alberto Boralevi from Florence; and May Beattie, Jon Thompson, and Michael Franses from Britain.

Several of these speakers were and still are Hajjis or at least honorary Hajjis, but these eminent individuals, many of

1. 45 At the 1954 Hajji Baba Summer Picnic.

1. 45 At the 1954 Hajji Baba Summer Picnic.

Arthur Dilley is the only Hajji wearing a coat, vest and tie. Joe McMullan is the Hajji in a state of undress

1.46 Joe McMullan escorting the Shah and Shahbanou of Iran at The Textile Museum in Washington D.C., 1964

1.46 Joe McMullan escorting the Shah and Shahbanou of Iran at The Textile Museum in Washington D.C., 1964

1.47 Joseph Reinis, President of the Hajji Baba Club, and other members at the Metropolitan Museum’s 1979 Thacher retrospective

1.47 Joseph Reinis, President of the Hajji Baba Club, and other members at the Metropolitan Museum’s 1979 Thacher retrospective

7. AFTER DILLEY – 1959 TO 1982.

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

1.48 Richard Ettinghausen

1.48 Richard Ettinghausen

1.49 Arthur D. Jenkins and Joseph V. McMullan

1.49 Arthur D. Jenkins and Joseph V. McMullan

1.51 Hajjis Maurice Dimand, Dennis R. Dodds, Olive Foster and Charlie Ellis

1.51 Hajjis Maurice Dimand, Dennis R. Dodds, Olive Foster and Charlie Ellis

at the Metropolitan Museum’s 1979 Thacher retrospective

of the 16th and 17th century from all the major carpet-producing countries. There were also people who bought carpets for utilitarian purposes for their homes or offices… They were very much appreciated for their own beauty, but there was a kind of dichotomy between the two: the classical carpets of the early period in the museums and outstanding private collections, and the rugs of the 19th century… found in private homes.” Then, Ettinghausen continued, “came Joe, and his contribution demonstrated that the two groups could go together… He realized the beauty of the so-called ‘village’ rugs, especially rugs from Turkey…” He further “realized that a late date did not mean that the rugs were degenerate” and urged carpet fanciers to expand their collections to include “the non-floor coverings, for instance, horse blankets, saddle bags, and other secondary types of carpet weaving,”29 thereby setting a brand new course for connoisseurs. The carpets – Classical Persian and Mughal pieces – that had,

since the days of Bardini and Bode, been regarded as the only ones worthy of a collector’s attention, suddenly found themselves joined centre stage by a whole range of previously-ignored weavings, objects that had been considered inconsequential. According to Ettinghausen, this was the aesthetic evolution Joe McMullan ignited.

Some of McMullan’s carpets were included in the ‘7000 Years of Iranian Art’ exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1964. It was during this exhibition that he had the privilege of escorting Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi of Iran (fig. 1.46), on a tour of The TextileMuseum’s collection, an experience he never tired of proudly describing. The Metropolitan Museum of Art showed McMullan’s collection in 1970 and then, in 1972, in the first large-scale exhibition of important carpets held in England since Pope’s 1931 extravaganza, a selection of his rugs was seen at London’s Hayward Gallery in a display devised and installed by the respected critic David Sylvester. At the opening of the exhibition, McMullan, echoing the philosophy of the Hajji Baba Club – on which he had had such an enormous influence during the forty years he had counted himself a member, but which likewise had consistently been at his side as he assembled his collection – spoke for all Hajjis: “This show is a real victory not for me but for all of us because carpets, which have been considered decorative pieces for so long, really now are acknowledged as being a true art form,”30 a statement that might even have convinced the ever-pessimistic Dilley that the good times had arrived.

CCC

CCC

Not only did McMullan use his own collection to promote carpets as art, but he also helped organise exhibitions that included rugs belonging to others. A prime example was the 1966 exhibition of Turkmen weavings at Harvard’s Fogg Museum, curated by his protégé and Club member, Christopher Reed, an exhibition that McMullan supported generously with both time and money. Aware that Amos Thacher’s book on Turkmen rugs had appeared when, because of the Second World War, few people were focused on rugs, McMullan understood that its impact had been slight. With the support of his fellow Hajjis, he was determined to correct that situation, to make the world aware of the glories of Turkmen carpet weaving, a mission the Fogg exhibition accomplished beyond even his expectations. Enormously influential, it is generally credited with setting into motion the series of events that would lead to a craze for Turkmen rugs, so-called ‘Turkomania’, that infected so many collectors not long thereafter.

McMullan’s death in 1973, a great loss for the Club and for the concept of rugs as art, failed to dampen the Hajji Babas’ enthusiasm for spreading the good news about carpets through exhibitions. To guarantee that no one missed the point of the 1966 Harvard exhibition, in 1979 the Club held a retrospective in honour of Thacher at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art (figs. 1.47, 1.51), including a display of thirty-eight pieces that had either belonged to him, or that he had illustrated in his 1940 study.

Then, in 1980, Hajji Alvin Pearson (fig. 1.52) developed the idea of, and provided much of the funding for, yet another Turkmen exhibition, this one held initially at The Textile Museum in Washington to coincide with the Third International Conference on Oriental Carpets, and then at the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey. Accompanied by a superb catalogue, Turkmen: Tribal Carpets and Traditions, edited by Louise W. Mackie and Jon Thompson, it closed in April 1981; by that time Turkmen weavings were hot items. n 1982, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the oldest Oriental rug club in the country, the Hajjis exhibited fifty of their rugs, first at New York’s Asia Society, which had just moved to 725 Park Avenue, and then at the Seattle Art Museum and the

Cincinnati Art Museum. The selection of rugs was made by Charlie Ellis and Daniel Walker, then Curator of Ancient, Near Eastern and Far Eastern Art in Cincinnati.Walker also authored the elegant catalogue that accompanied the exhibition. Al Pearson provided a planning grant to move the project forward, and BruceWestcott and Joe Reinis (fig. 1.47) supplied much of the necessary momentum to carry it to completion.

1.53 Charles Grant Ellis acquired this rare so-called ‘Para- Mamluk’ rug, now in an Italian collection,

1.53 Charles Grant Ellis acquired this rare so-called ‘Para- Mamluk’ rug, now in an Italian collection,

too late for selection for the Hajji Babas’ Fiftieth Anniversary show at New York’s Asia Society in 1982.

Courtesy Moshe Tabibina, Milan

8. DIVIDED AND REUNITED

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

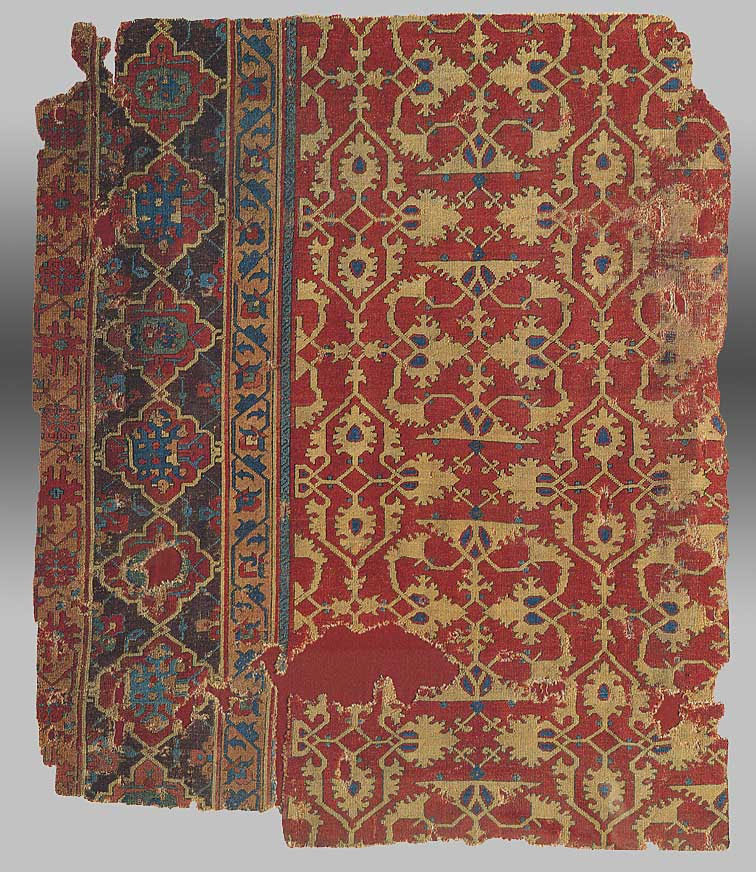

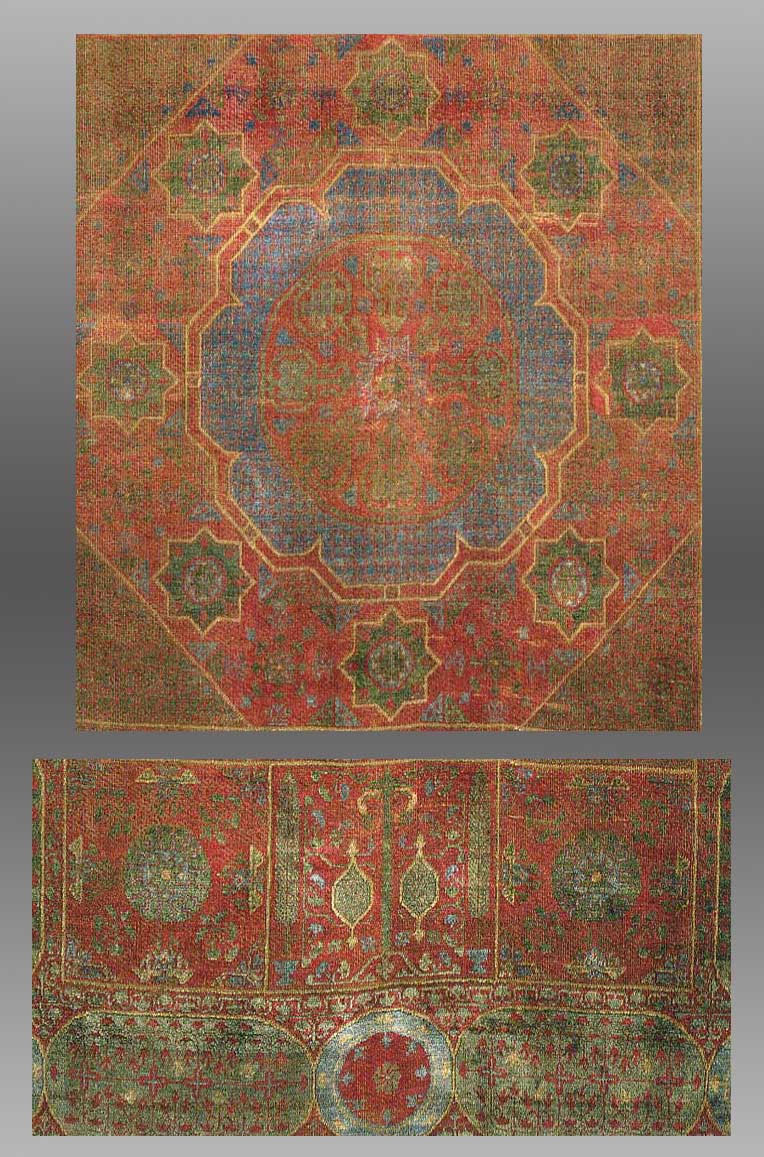

1.54 (above, detail below) Ushak ‘Lotto’ carpet fragment, loaned to the Brooklyn Museum for exhibition during the 1996 post-ICOC NewYork tour.

1.54 (above, detail below) Ushak ‘Lotto’ carpet fragment, loaned to the Brooklyn Museum for exhibition during the 1996 post-ICOC NewYork tour.

Marshall &Marilyn R. Wolf Collection

1.55 (above with further details below)

1.55 (above with further details below)

Detail of a Mamluk rug, exhibited in Brooklyn during the 1996 post-ICOC New York tour.

Brooklyn Museum, New York, Gift of Mr & Mrs Frederic B. Pratt, no. 43.24.3.

9. TOWARDS THE 21ST CENTURY

1. The First Hajji

2. The Founding Fathers

3. Moguls and Merchants

4. Demotic Devolution

5. The Club’s Early Years

In 1992, two latter-day Hajjis, R. DeWittMallary and Robert Pittenger (fig. 1.66), aided and abetted by honorary curator Hajji Newton Foster, organised an exhibition and prepared a slim catalogue of twenty-five of Hajji W. Parsons Todd’s rugs at the Maccullough Hall Historical Museum in Morristown, New Jersey.33 At least two of the Todd rugs on display had once belonged to Arthur Dilley.

Four years later, in November 1996, the Eighth International Conference on Oriental Carpets met in Philadelphia (fig. 1.56). That occasion provided what many Hajjis believed to be the perfect opportunity not just for an exhibition but for a whole series of events to celebrate carpets and textiles in New York City (figs. 1.57, 1.58). Co-sponsored by Christie’s and Sotheby’s, the celebration began with exhibitions at those two auction houses, followed in close succession by the opening of the Hajji Baba Club’s show, ‘A Skein through Time’, at Baruch College, and then by a Club-sponsored Middle Eastern dinner at the National Arts Club. The Hajji exhibition, curated by Arlene J. Lederman, Daniel Walker, and Marilyn Wolf, which was accompanied by an eponymous catalogue, displayed forty-five members’ rugs and textiles.

The following morning, the Hajjis escorted their guests to the Brooklyn Museum, whose holdings (fig. 1.55) were enhanced by Classical carpet loans (fig. 1.54) from the collection of Hajjis Marshall and Marilyn Wolf, and that afternoon to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see seldom-seen carpets as well as Islamic textiles, once again from the Wolf Collection. As HALI magazine later reported, “It’s quite an accolade for objects belonging to a living private collector to be seen inside the august portals of the Met, let alone for a gallery to be devoted to them and for the collector’s name to appear on MMA posters out on Fifth Avenue.” The report continued: “The Met’s selection of Islamic textiles from the Wolf Collection was itself a trailblazer. Never before in the history of the MMA had a humble kilim been allowed to show its face on such hallowed ground. Too ethnic. But here we found two of these lowly objects – both Wolf cubs.”34

Once again Hajjis, this time the Wolfs, self-educated connoisseurs, were, as had McMullan and the other early Hajjis, moving along well ahead of the pack, seeing new opportunities, taking risks, pushing boundaries, and bringing overlooked treasures to the attention of more conventional collectors. One might even argue that this was, according to well-established precedent, what Hajjis were supposed to do.

1.56 Hajji Brooke Pickering among Moroccan rugs from the Pickering/Yohe Collection

1.56 Hajji Brooke Pickering among Moroccan rugs from the Pickering/Yohe Collection

exhibited at the Philadelphia International Conference on Oriental Carpets in 1996

1.57 Sometime Hajji President Barry Jacobs with Hajji Mary Hammond Sullivan at the 1996 Philadelphia ICOC

1.57 Sometime Hajji President Barry Jacobs with Hajji Mary Hammond Sullivan at the 1996 Philadelphia ICOC

1.58 Hajji Marc Feldman, lender to the Hajji exhibition ‘A Skein Through Time’ in 1996.

1.58 Hajji Marc Feldman, lender to the Hajji exhibition ‘A Skein Through Time’ in 1996.

1.59 A Yomut Turkmen tent-bag front exhibited at the 1996 Philadelphia ICOC Nancy Jeffries & Kurt Munkacsi.

1.59 A Yomut Turkmen tent-bag front exhibited at the 1996 Philadelphia ICOC Nancy Jeffries & Kurt Munkacsi.

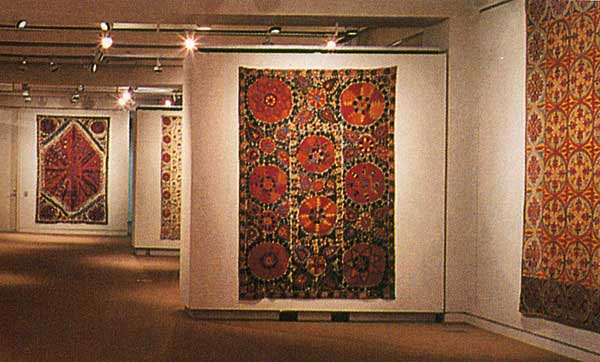

1.62 Hajjis Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf’s collection of suzani embroideries was exhibited at Sotheby’s in 2003.

1.62 Hajjis Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf’s collection of suzani embroideries was exhibited at Sotheby’s in 2003.

1.60 The Wolf Collection of Central Asian suzani embroideries was shown at Sotheby’s during the 2003 post-ICOC tour of New York

1.60 The Wolf Collection of Central Asian suzani embroideries was shown at Sotheby’s during the 2003 post-ICOC tour of New York

In 1992, two latter-day Hajjis, R. DeWittMallary and Robert Pittenger (fig. 1.66), aided and abetted by honorary curator Hajji Newton Foster, organised an exhibition and prepared a slim catalogue of twenty-five of Hajji W. Parsons Todd’s rugs at the Maccullough Hall Historical Museum in Morristown, New Jersey.33 At least two of the Todd rugs on display had once belonged to Arthur Dilley.

Four years later, in November 1996, the Eighth International Conference on Oriental Carpets met in Philadelphia (fig. 1.56). That occasion provided what many Hajjis believed to be the perfect opportunity not just for an exhibition but for a whole series of events to celebrate carpets and textiles in New York City (figs. 1.57, 1.58). Co-sponsored by Christie’s and Sotheby’s, the celebration began with exhibitions at those two auction houses, followed in close succession by the opening of the Hajji Baba Club’s show, ‘A Skein through Time’, at Baruch College, and then by a Club-sponsored Middle Eastern dinner at the National Arts Club. The Hajji exhibition, curated by Arlene J. Lederman, Daniel Walker, and Marilyn Wolf, which was accompanied by an eponymous catalogue, displayed forty-five members’ rugs and textiles.

The following morning, the Hajjis escorted their guests to the Brooklyn Museum, whose holdings (fig. 1.55) were enhanced by Classical carpet loans (fig. 1.54) from the collection of Hajjis Marshall and Marilyn Wolf, and that afternoon to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see seldom-seen carpets as well as Islamic textiles, once again from the Wolf Collection. As HALI magazine later reported, “It’s quite an accolade for objects belonging to a living private collector to be seen inside the august portals of the Met, let alone for a gallery to be devoted to them and for the collector’s name to appear on MMA posters out on Fifth Avenue.” The report continued: “The Met’s selection of Islamic textiles from the Wolf Collection was itself a trailblazer. Never before in the history of the MMA had a humble kilim been allowed to show its face on such hallowed ground. Too ethnic. But here we found two of these lowly objects – both Wolf cubs.”34

Once again Hajjis, this time the Wolfs, self-educated connoisseurs, were, as had McMullan and the other early Hajjis, moving along well ahead of the pack, seeing new opportunities, taking risks, pushing boundaries, and bringing overlooked treasures to the attention of more conventional collectors. One might even argue that this was, according to well-established precedent, what Hajjis were supposed to do.

1.61 Detail of the ‘Emperor’s Carpet’, one of the rarely-seen Safavid Persian carpets shown

1.61 Detail of the ‘Emperor’s Carpet’, one of the rarely-seen Safavid Persian carpets shown

to the Hajji’s post-ICOC Metropolitan Museum tour groups in 2003 by curator

Daniel Walker. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, no. 43.121

In 1992, two latter-day Hajjis, R. DeWittMallary and Robert Pittenger (fig. 1.66), aided and abetted by honorary curator Hajji Newton Foster, organised an exhibition and prepared a slim catalogue of twenty-five of Hajji W. Parsons Todd’s rugs at the Maccullough Hall Historical Museum in Morristown, New Jersey.33 At least two of the Todd rugs on display had once belonged to Arthur Dilley.

Four years later, in November 1996, the Eighth International Conference on Oriental Carpets met in Philadelphia (fig. 1.56). That occasion provided what many Hajjis believed to be the perfect opportunity not just for an exhibition but for a whole series of events to celebrate carpets and textiles in New York City (figs. 1.57, 1.58). Co-sponsored by Christie’s and Sotheby’s, the celebration began with exhibitions at those two auction houses, followed in close succession by the opening of the Hajji Baba Club’s show, ‘A Skein through Time’, at Baruch College, and then by a Club-sponsored Middle Eastern dinner at the National Arts Club. The Hajji exhibition, curated by Arlene J. Lederman, Daniel Walker, and Marilyn Wolf, which was accompanied by an eponymous catalogue, displayed forty-five members’ rugs and textiles.

The following morning, the Hajjis escorted their guests to the Brooklyn Museum, whose holdings (fig. 1.55) were enhanced by Classical carpet loans (fig. 1.54) from the collection of Hajjis Marshall and Marilyn Wolf, and that afternoon to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see seldom-seen carpets as well as Islamic textiles, once again from the Wolf Collection. As HALI magazine later reported, “It’s quite an accolade for objects belonging to a living private collector to be seen inside the august portals of the Met, let alone for a gallery to be devoted to them and for the collector’s name to appear on MMA posters out on Fifth Avenue.” The report continued: “The Met’s selection of Islamic textiles from the Wolf Collection was itself a trailblazer. Never before in the history of the MMA had a humble kilim been allowed to show its face on such hallowed ground. Too ethnic. But here we found two of these lowly objects – both Wolf cubs.”34

Once again Hajjis, this time the Wolfs, self-educated connoisseurs, were, as had McMullan and the other early Hajjis, moving along well ahead of the pack, seeing new opportunities, taking risks, pushing boundaries, and bringing overlooked treasures to the attention of more conventional collectors. One might even argue that this was, according to well-established precedent, what Hajjis were supposed to do.

1.64 Rugs from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum laid out in the museum’s grand

1.64 Rugs from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum laid out in the museum’s grand

courtyard for the 2003 post- ICOC New York tour arranged by the Hajji Baba Club.

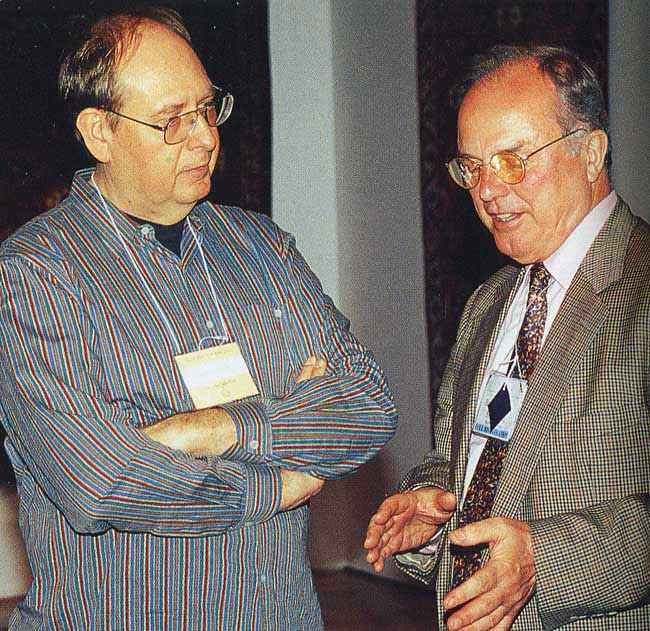

1.63 Hajji Kurt Munkacsi (President of the Club in 2008) discussing Turkmen weaving with German collector Hans-Christian Sienknecht

1.63 Hajji Kurt Munkacsi (President of the Club in 2008) discussing Turkmen weaving with German collector Hans-Christian Sienknecht

at the exhibition of Munkacsi’s Turkmen main carpets in the Mark Shilen Gallery during the 2003 post-ICOC tour.

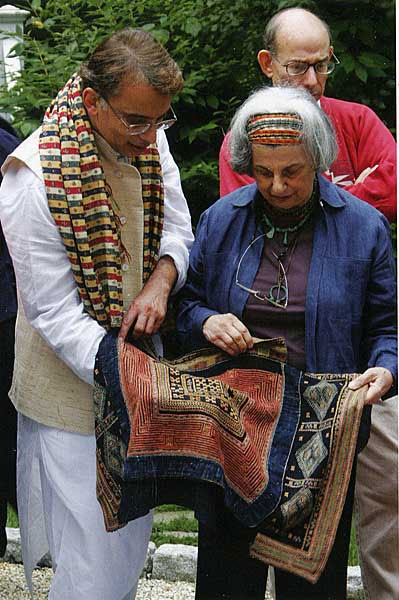

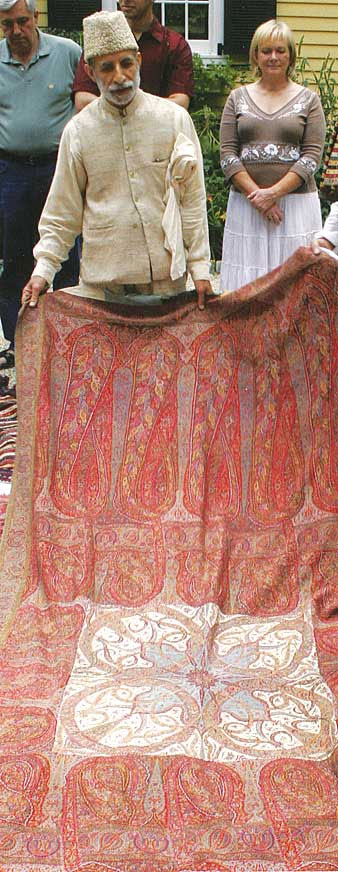

1.65 The annual summer picnic remains an important Club fixture:

1.65 The annual summer picnic remains an important Club fixture:

Hajjis Vinay Pande (wearing a Kashmir shawl) and Mae Festa

examine a tribal embroidery at the 2006 picnic.

1.66 Robert Pittenger, Carol Ascher and former Hajji

1.66 Robert Pittenger, Carol Ascher and former Hajji

President Joseph P. Doherty at the 2006 picnic

1.67 Hajji Basha Ahamed lends a willing hand in

1.67 Hajji Basha Ahamed lends a willing hand in

the 2006 summer picnic ‘show-and-tell’

NOTES

1. Olive Olmstead Foster, Fine Arts, Including Folly: A History of the Hajji Baba Club, 1932-1960, New York, 1966, p. 8.

2. Ibid., p. 11.

3. Ibid., p. 12.

4. Ibid.

5. Arthur U. Dilley, How Oriental Rugs Are Sometimes Sold, Boston 1906, p. 16.

6. Foster, op.cit., p. 8.

7. Ibid., p. 9.

8. Ibid., p. 10.

9. Arthur U. Dilley, ‘Clio’s Scrolls’,” in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.

10. Foster, op.cit., p. 10. See also Barry Jacobs, ‘A Rogue’s Progress’, Hali 32, October/November/December1986, pp.12-17.

11. Daniel S. Walker, Oriental Rugs of the Hajji Babas, New York, 1982, p. 14.

12. Foster, op.cit., p. 19.

13.Wesley Towner, The Elegant Auctioneers, New York, 1970, p. 29.

14. Meryle Secrest, Duveen, A Life in Art, New York, 2004, p. 45.

15. Times, London, January 7, 1931.

16. Foster, op.cit., p. 2.

17. Nahigian Brothers, Oriental Rugs in the Home, Chicago, 1913, p. 5.

18. William M. Butler, Rugs of the Orient, Philadelphia, 1913.

19. Joseph V. McMullan, ‘The Hajji Baba Rug’, in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Foster, op.cit., p. 19.

24. Ibid., pp. 31-33.

25. Harold Weaver, ‘Derkazarian Rugs’, in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.

26. Foster, op.cit., p. 13

27. Both of Dilley statements are quoted in William Russell Pickering, Don’t forget to smell the flowers along the way, Portraits of Joseph V. McMullan, New York, 1977, p. 55.

28. Ibid., p. 58.

29. Ibid., pp. 69-70.

30. McMullan’s remarks are in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.

31. W.R. Pickering to Maurice A. Dimand, 13 April 1970, in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.

32. Joseph V. McMullan, Richard Ettinghausen, Marilyn Jenkins, Ralph S. Yohe, Marie Grant Lukens, and Donald N. Wilber to the Executive Committee of the Hajji Baba Club, 10 November 1970, in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.

33. Robert Pittenger & R. DeWitt Mallary, Oriental Rugs from the Collection of W. Parsons Todd, New York, 1992.

34. Hali 92, May 1997, p. 104.

35. Ibid., p. 105.

36. Ernst J. Grube, Keshte: Central Asian Embroideries, The Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf Collection, New York, 2003.

37. Brantley’s letter is in the Hajji Baba Club Archives.